![]() CLIQUEZ ICI POUR LIRE LA TRADUCTION FRANÇAISE

CLIQUEZ ICI POUR LIRE LA TRADUCTION FRANÇAISE

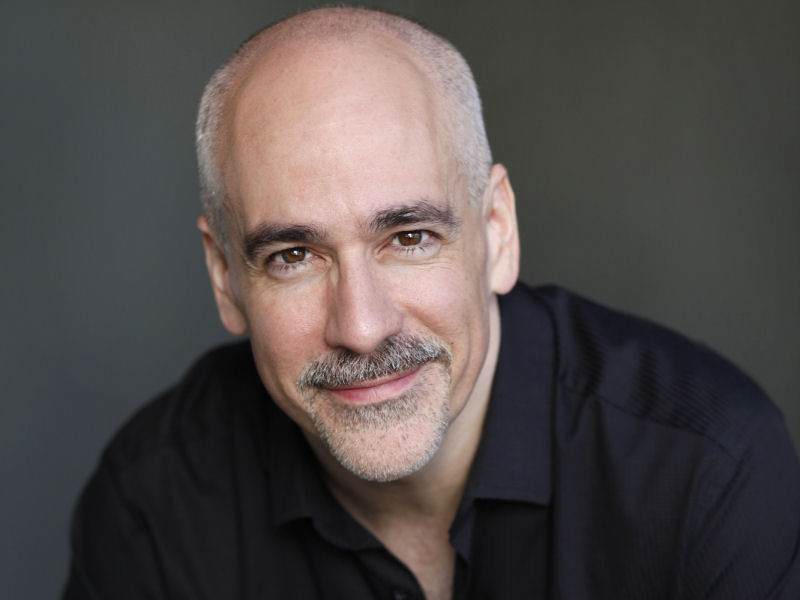

American composer Peter Boyer has been noted since his student years in the 90s for the quality of his orchestral work, often described as lyrical, energetic and powerful. He has become one of the most frequently performed American orchestral composers of his generation, with over 400 performances of his works by more than 150 orchestras, including several of the major American orchestras.

He has conducted three albums of his concert music with the London Symphony Orchestra, the Philharmonia Orchestra and the London Philharmonic Orchestra (two of these for Naxos), all of which have received extensive broadcasts on classical radio throughout the United States and abroad. His major work, Ellis Island: The Dream Of America, for actors and orchestra, is one of the most performed large-scale American concert works of the last 15 years in the U.S., with over 160 live performances, and it received a Grammy nomination for Best Contemporary Classical Composition.

In addition to his work for the concert hall, Boyer is active as an orchestrator for Hollywood films, having worked on more than 35 feature film scores for several leading Hollywood composers, including Michael Giacchino, James Newton Howard, Thomas Newman, James Horner and Mark Isham. Boyer agreed to answer to our questions about his work as a concert composer, and an orchestrator for movies.

Can you share some memories about the path that led to you to become a composer?

My childhood did not include serious music study, though I did take some lessons in guitar (pop, not classical) around age 10 to 11. As a teenager, I was a huge fan of several popular American singer-songwriters, such as Billy Joel (first and foremost), Paul Simon, Dan Fogelberg, and others, and pop/rock groups such as Journey and the Eagles. So American popular music was primarily what I listened to, and this became the formative influence in my earliest days as a young musician. When I began playing the piano and composing, at age 15 in high school, it was in this pop music genre. I started as an aspiring singer-songwriter, and gave my first public performances of this sort soon after, in my native Rhode Island. I took to the piano and composing fairly naturally, though I was a late starter, and music became the dominant interest in my life starting then. I should mention that I did not end up becoming much of a pianist, and never seriously pursued performing classical repertoire, though I did end up playing popular music on many professional gigs during my later student years.

When I was in my junior year of high school, just turning 17, a couple events coincided which ended up having a big impact on me. I was taking a music history course, and learning something about classical music and composers for the first time. My paternal grandmother, who had gotten me my first piano and arranged for my first music lessons, died suddenly, and at that same time, I heard the Mozart Requiem for the first time in this music history class. So I got in my head the crazy idea that I would compose a Requiem Mass, and dedicate it to my grandmother’s memory. Not having a composition teacher (I didn’t have formal composition lessons until I went to graduate school), I took scores and recordings of Requiem Masses by various composers out of my local library, starting studying them, and started composing one. It’s a long story, but three years later, I had just turned 20 and was a junior at Rhode Island College, I conducted the premiere of my 40-minute Requiem with soloists, orchestra, and choir — about 300 performers in total. I had received a great deal of support from teachers, administrators, and community members, without whom I could not have done this.. But essentially, I was this insanely ambitious teenage composer, and managed to do this, which was my first major piece of concert music. It received a great deal of media attention, including recognition by the national USA Today newspaper, and the response in my community was overwhelming. I was just a college student, but this was a formative experience on my path to becoming a composer.

https://youtu.be/1X4Q7LWV4ig[/youtube

So it was only in graduate school that you received your first formal composition lessons?

That’s correct. I actually composed several more large-scale concert works during my junior and senior years of college, including a cantata for soloist, choir, and orchestra, while still having no formal composition teacher, though I did have guidance from my undergraduate teachers. I went on to do graduate studies (M.M. and D.M.A. degrees) at the Hartt School of Music, a conservatory which is part of the University of Hartford. There I studied composition for one year with Robert Carl, and for three years with Larry Alan Smith (who had been a pupil of Vincent Persichetti at Juilliard, and also had studied with Nadia Boulanger). Larry was my principal composition teacher. I also studied conducting for three years with Harold Farberman, one of the better-known American conducting teachers, who is also a very accomplished composer. I learned a huge amount during these intense years of study, which were formative times for me.

Your training also included studies with composers John Corigliano and Elmer Bernstein…

After I completed my doctorate at Hartt, I studied privately with John Corigliano in New York. I had met him at the Conductors Institute when I was a conducting student there, and admired his work greatly. After I won the BMI Student Composer Award for the first time, I got back in touch with him, and asked if he would accept me as a private student once I finished my formal graduate study, and he agreed. I studied with him for just one summer, but even this fairly brief period of work with him made a huge impression on me. He is, of course, a master composer of the highest caliber, with a unique approach to composition and orchestration.

Following that period, I relocated to Los Angeles, and completed the one-year program in Scoring for Motion Pictures and Television at the USC (now Thornton) School of Music, which is where I met and studied with Elmer Bernstein, among others. Elmer was, of course, a master composer of a different sensibility, a great musical dramatist, and also a very kind man. He actually took quite an interest in my concert music and my conducting, and I conducted his short film score Toccata For Toy Trains live to a 16mm print a couple times in his presence, which pleased both him and me greatly! Among other things, I recall that after playing for him a recording of my just-completed piece New Beginnings, with a big smile on his face, he said, “Well, Peter, I would describe that piece as a series of excitements!” That meant a lot to me. He is greatly missed. I suppose the fact that I did this one-year SMPTV program at USC after having completed a doctoral degree showed that my dual interests in concert music and film music were there even then.

Do you have some favorite composers from different historical periods?

There are so many! I’ll mention several, grouping them in some basic ways. Mid-20th century Americans: Copland, Bernstein, Barber, Hanson; Europeans and Russians: Britten, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Shostakovich; earlier in the 20th century (with a bit of the late 19th century): Mahler, Ravel, Debussy, Sibelius, Vaughan Williams. Going back to the classical era, I certainly listen to plenty of Beethoven, Haydn and Mozart, with, perhaps not surprisingly, an emphasis on the Beethoven symphonies. I listen to quite a bit of contemporary American orchestral literature, covering at least a couple generations of composers: John Adams, John Corigliano, Joseph Schwantner, the late Stephen Albert, Richard Danielpour, Michael Daugherty, Michael Torke, Kenneth Fuchs, Kevin Puts, Jennifer Higdon. I listen very often to John Williams — both his film music and his concert music. In the genre of film music, there are so many composers whose work I enjoy. Besides John Williams, the late Jerry Goldsmith and Elmer Bernstein stand out as important figures for me. I’m a huge admirer of James Newton Howard, Thomas Newman, and the late James Horner (and consider myself very fortunate to have orchestrated for all three of them). Though it’s in a different genre, I should mention that I’m an enormous admirer of Stephen Sondheim’s musical theater works. There are many other composers whose work I enjoy as well.

Do you agree that your musical style is recognizably American, demonstrating influences from major American symphonic composers, from Copland and Leonard Bernstein to John Williams?

The short answer is yes. Of course, it is both a great honor and a daunting thing for any American orchestral composer to have one’s work mentioned in the same breath as that of Copland, Bernstein, and Williams. As it happens, these three composers are certainly the ones referenced most often by journalists and critics in writing about my music. I suppose that these influences on my voice are unmistakable, though it’s my hope that my own music would never be seen merely as imitation or pastiche. The reality is that the music of each of these three composers is personally very important to me — I have the greatest admiration and respect for their work, and I’ve spent a huge amount of time over the years studying and simply enjoying their music, along with that of Barber, Hanson, and other key 20th-century American composers. So perhaps it was inevitable that some of this specific American orchestral vocabulary would find its way into my music. I have also received a number of commissions for which the occasions or subject matter seemed to make this kind of approach natural — Ellis Island: The Dream Of America, or the Kennedy Brothers commission for the Boston Pops, as two examples.

Your music, while very deep, never sounds like “intellectual” music. Everyone can enjoy it. Is this something you do consciously? And it seems to “flow” very naturally, does it come easily to you?

I believe that music is a form of communication, and that the connection which music can make between composer, performers and listeners is one of the most profound artistic experiences we can have as human beings. I also believe strongly in the power of melody. Much of my music is lyrical and tuneful (a word that various writers have used to describe it, I think accurately). I believe that I am fortunate in having an innate ability to write tunes fairly naturally, and I don’t think this is something that can be taught: either one can do that or one can’t. I’m grateful that I can. Going back to a couple of American composers, Bernstein and Williams, what incredible gifts each had/has with writing melodies which listeners can readily grasp, embrace, and remember. This is part (though only part) of what makes them so special as composers. The writing of memorable, lyrical lines is something which I admire, and to which I aspire.

That being said, the ability to sit down at a piano and improvise attractive melodies or themes, while very important and useful, is not sufficient to create a piece of music that flows and feels organic as it moves from Point A to Point B to Point C. That requires craftsmanship, revisions and tenacity — the shaping of an initial melodic or thematic idea or ideas into a musical structure that works, drawing upon one’s knowledge of, and experience with, so much great music that has come before. This is a very subjective process, but it’s a crucial part of one’s work as a composer — continuing to build, combine, and refine musical ideas until one has created something that feels right and satisfying. And that’s not even speaking of the process of orchestration. So, while the initial ideas may come easily, what follows inevitably involves a great deal of work!

Can you describe your composition process?

That’s a big question. The process for me has changed over the years, as advances in technology have added capabilities to the composition workflow. There is also an important distinction between my process in composing concert music and composing to picture/video (I’ve done much more of the former than the latter). In my earlier orchestral compositions, I would sketch themes in pencil on manuscript paper at the piano, then go to Finale software and create a complete sketch on four or five staves. Once the sketch was complete, I would move on to the orchestration in full score, again in Finale. For a number of my earlier works, such as Ellis Island, Three Olympians, and New Beginnings, this was the process I used. My playback during the composing process at that time was simply a sampled piano sound, I was not attempting elaborate orchestral simulations or mock-ups with software, and didn’t actually hear the orchestration (outside of my imagination) until the first rehearsal. Though things have changed, it’s worth noting that this process did seem to work successfully enough: works of mine which have had a significant life on the concert stage and on classical radio were written this way.

For the last few years, I’ve been using an elaborate composing template with Sibelius notation software and a playback configuration which includes Vienna Ensemble Pro software hosting a large collection of instruments from the Vienna Symphonic Library. The developers at VSL have created sound sets which allow a great deal of realistic playback of their virtual instruments right from Sibelius software (as opposed to sequencing software). Since I tend to think in musical notation (as opposed to graphic or piano roll notation in a sequencer), I find this to be a helpful way to work in composing orchestral music. So, in addition to hearing the lines, I’m composing in my orchestral score played by specific woodwind, brass, strings or percussion instruments which sound reasonably realistic, as I’m writing them, the virtual instruments respond to notational elements in the score. As a few examples: entering crescendo or diminuendo hairpins in the score results in playback that sounds fairly realistic, triggering crossfades with timbral changes programmed into the virtual instruments; entering slurs, accents or other articulations in the score results in playback that automatically selects the appropriate samples; typing con sordino triggers samples with mutes, etc. The bottom line is that entering notational elements in the Sibelius score, which look as they should to achieve the desired results in the real world, also achieves those results in the playback of the samples while composing, without having to do any sequencer-type programming. I have found this to be a very useful tool for orchestral composition.

When I’m composing to picture (which I’ve done much less often than composing concert music), then I use sequencing software, along with an elaborate set of sample libraries, including the VSL libraries I just described, and a number of others. I have used both Digital Performer and Pro Tools software for composing to picture.

Do you work every day?

As far as schedule goes, this can vary significantly. I tend to compose concert music only when I have a commission to do so. When I don’t have a specific commission in front of me, I tend to spend my time promoting my existing catalog of work, pursuing my next projects, doing film orchestration work, etc. When I do have a commission for a concert work, the timeline for that commission dictates my writing schedule. As the commission deadline draws nearer, the amount of hours per day spent on composing tends to increase, and a looming deadline always acts as a motivator and catalyst to focus the mind on what must be done.

Your work often seems to focus on celebrations…

It’s true that my catalog of orchestral works has a sizeable component of celebratory music. I suppose the reason for this is twofold: I’m naturally drawn to compose such music, and I have had a number of commissions for celebratory occasions, which of course demand music appropriate to those occasions. Thinking of four such works from my catalog, each was in response to a specific commission celebrating a particular event: Celebration Overture for the opening of the Henry Mancini Institute in Los Angeles; New Beginnings for the opening of The New Bronson Hospital in Kalamazoo, Michigan; Silver Fanfare for the 25th anniversary of Orange County’s Pacific Symphony (part of the larger work On Music’s Wings); and Festivities for the 50th anniversary of the Eastern Music Festival in Greensboro, North Carolina. Composing celebratory, occasional pieces is certainly something I enjoy, and for which I have an affinity, though this is only one aspect of my interests as a composer.

Your work is played very frequently by American orchestras. How do you explain its popularity?

I’d like to think that the answer has to do with some combination of quality and craftsmanship in the music, along with an accessibility that makes the music attractive to listeners. And certainly I have spent a great deal of time in my life engaged in promotion of the music, both to conductors and to orchestra administrators. Those have been investments of time and energy which have paid off, I think. But of course, apart from any promotion, the quality of the music has to be primary.

Your Symphony No. 1 is a classical three-movement symphony. What was your inspiration?

Having composed a number of orchestral works which were programmatic, or commissioned to celebrate specific occasions or themes, I decided a few years ago that I wanted to undertake the challenge of composing a non-programmatic symphony. It really was more of a personal challenge than anything else: to see if I could successfully compose such a work, that was simply about the notes themselves, and the relationships between them, rather than any external program or theme. I was able to secure a commission from the Pasadena Symphony in the Los Angeles area for a work of about 24 minutes, with no other parameters specified. Initially, I thought that the work would be in four movements, and sketched material for a fast-tempo finale movement. However, as I kept working on the Adagio third movement, it kept growing, and eventually I found a way in which I believed this could evolve to become a satisfying ending. So ultimately, I settled on a three-movement structure. Interestingly, though this was not a conscious modeling, the first symphonies of both Copland (his Symphony for Organ and Orchestra of 1924) and Bernstein (his Jeremiah Symphony of 1942) are three-movement symphonies of similar duration.

I decided, while in the process of composing this work, that I would dedicate it to the memory of Leonard Bernstein, whose work, of course, was so influential on me in many ways. For some years now, I have been friendly with his daughter Jamie, and I told her of my wish to make this dedication, but only if it would be something that would be welcomed by her family. Happily, she spoke with her two siblings, and the Bernstein children graciously accepted this dedication; and she then provided me with a lovely statement of support and congratulations on the work. As you know, my Symphony No. 1 became the centerpiece of my third recording, which I recorded with the London Philharmonic Orchestra at Abbey Road Studios, and which was released by Naxos (along with four other works of mine). This was an incredibly rewarding experience for me, and happily Naxos gave the work a lot of promotion and attention, and the symphony has been broadcast quite extensively since its release in early 2014.

Would you say that The Dream Lives On: A Portrait Of The Kennedy Brothers (2010) is a sort of marriage between concert music and film music?

Well, this work is a piece of concert music with narration from speeches by John, Robert, and Ted Kennedy, and it did have a significant visual component in its performances with the Boston Pops, taken from archival materials from the Kennedy Library. So I suppose that one could call it “cinematically influenced concert music.” It is actually similar in musical vocabulary and tone to my work Ellis Island: The Dream Of America — which, it turns out, was the reason why Boston Pops conductor Keith Lockhart chose me for the Kennedy Brothers commissioning project. And of course, it was incredibly exciting to have Hollywood actors Robert De Niro, Ed Harris, and Morgan Freeman all narrate my work for the premiere at Symphony Hall in Boston, and for the recording and telecast. Later, Alec Baldwin narrated the work solo at Tanglewood. It was, without a doubt, one of the most exciting and rewarding opportunities I’ve ever had as a composer.

Is conducting your own music a part of the recording process that you enjoy?

Absolutely! Conducting was a significant part of my training — I mentioned my three years of study with Harold Farberman — and it has been part of my work for a long time, though in recent years I have done less of it, focusing on other aspects of my career. Composing and orchestrating are such solitary pursuits… One spends so much time alone in one’s studio, creating and crafting the music, which eventually the musicians will bring to life. Conducting one’s own music can be a kind of joyful reward, brief though it may be, for the huge numbers of hours spent in getting that music right. I have been fortunate to have recorded my music with the London Symphony Orchestra, the Philharmonia Orchestra, the London Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Hollywood Studio Symphony — each of these of course being world-class orchestras. It’s almost impossible to describe how thrilling and rewarding those experiences have been for me, and in three of those cases, the recording process was documented through videos. Of course, we also live in a video-driven time, so these serve not only as documents of the recording process, but also as promotional tools for the music.

You created Propulsive Music, your own publishing company, in 2003. Can you explain why?

I created Propulsive Music for the same purpose that so many composers create their own publishing companies: to serve as a legal entity which holds the copyrights to one’s compositions, and which receives the publisher’s share of performance royalties from a performing rights society — BMI, in my case. Though today a very small percentage of living composers are represented by the major classical publishing companies, which hold the copyrights to their works — such as John Adams by Boosey & Hawkes/Hendon Music, or John Corigliano by G. Schirmer, as two notable examples — it has become common for many working composers to create their own publishing companies. When I did this, I also launched the first version of PropulsiveMusic.com — which happily was completely upgraded and re-launched a few months ago.

Since 2009, the publishing agent for my Propulsive Music catalog is Bill Holab Music, which also represents the catalogs of a number of prominent American classical composers who are also presently self-published, such as Kevin Puts, Michael Torke, Jake Heggie, Michael Daugherty, Richard Danielpour, and others. BHM handles all my rentals to orchestras — something I used to do myself, until the volume became too time-consuming — and that frees up more of my time to do creative or other work. It’s also worth noting that the availability of powerful music notation software such as Sibelius and Finale has made it possible for the orchestral scores and parts produced by self-published composers to equal in quality the materials produced by major publishers, which is a key factor in making self-publishing viable.

One of the first major motion pictures you worked on as an orchestrator was Michael Kamen’s Open Range. What do you remember about this experience, and about him?

Yes, three of my earliest film orchestration credits were on projects which turned out to be among Michael Kamen’s last: Against The Ropes, Open Range, and First Daughter (the movie score on which he was working when he died, completed by Blake Neely). I was pretty young, in my early 30s, and to me, Michael Kamen was a larger-than-life figure. I was fairly in awe of his body of work, and he was the first A-list composer for whom I had the opportunity to orchestrate. At that stage, having been given that opportunity, I think I was most concerned not to screw anything up! I was fortunate to visit him at his homes both in Los Angeles and in London (when I was there in 2003 to record the orchestral tracks to my Ellis Island with the Philharmonia), and I was pretty dazzled by those experiences. He was such a gifted and prolific man, with a great sense of musical drama. He died not too long after, and it was a great loss for so many, of course. I did not have the opportunity to spend much time with him, but I’m grateful that I knew him and worked with him, even if for a short time.

What is exactly your job as an orchestrator in Hollywood? And is there any truth in the myth of orchestrators doing ghostwriting for Hollywood composers?

This is quite a big question, which requires a long answer! The nature of the orchestrator’s role on film scores has changed significantly from its earlier years to now, due to changes in technology, and what possibilities exist today. The role of film orchestrator can vary significantly from composer to composer, and from project to project. One aspect of this work which I have very much enjoyed is that, in working with a number of extremely talented and prolific composers whose music I admire and respect, I have had the opportunity to look inside their workshops, so to speak — to get inside each composer’s particular musical vocabulary and approach in a detailed way. I can say that each film composer for whom I have worked has a process which is specific to him, so there are clear differences from one composer’s workflow to another. There are also commonalities, of course.

If one thinks back to the role of the film orchestrator in, say, the Golden Age — or in any era prior to the emergence of tools such as MIDI, sequencers, sample libraries, notation software, and the like — the task could be seen as a more conventional one, in that a composer wrote pencil sketches in which he notated the music and indications of instrumentation, and the orchestrator then fleshed out the sketches into full scores, which were passed on to the copyists. Of course, sketches could be more or less detailed, which therefore could mean that the orchestrator had to make more or fewer choices about voicings, doublings, articulations, etc., depending on what exactly he was given. When one thinks of some of these great figures of the Golden Age — Steiner or Korngold, as just two examples — of course these composers were fully capable of executing their own orchestrations: it was merely a question of time, or lack of it, in the scoring process.

Whereas film composers in these earlier eras would demonstrate their scores simply on the piano, and the full orchestral sound would not be heard until the actual scoring session, as you know, today technology has changed the game profoundly. Because sequencing software/digital audio workstations and immensely detailed orchestral sample libraries exist — and are getting better all the time — now it is possible for composers to create detailed demos or mock-ups of each cue on a film score, which can be incredibly realistic. Because of this capability, detailed mock-ups are now expected for every cue on major films, and in most cases must be approved by the director prior to orchestration and recording.

This has changed the nature of the orchestration process, because now there generally exists an extremely detailed recording of an orchestral mock-up as a reference, and the orchestrator must refer to that mock-up/demo very carefully in creating the orchestral score. As a general rule, today the orchestrator is given that mock-up audio file (and sometimes audio files of the separate orchestral stems: woodwinds, brass, strings, percussion, keyboards), and also a MIDI file which contains all the MIDI data that were used in the composer’s sequence, to trigger all the samples which were played and mixed to make that mock-up. On the one hand, it’s easy to see that with such detailed orchestral demos, the composer has indicated, through programming all these samples, what the orchestration should be, to a large extent. One might think that this renders the orchestrator to be more or less a transcriber, and there is some truth in that: accurate transcription is absolutely a big part of the job.

On the other hand, still there are many things which must be done to transform the MIDI data which were used in the mock-up into a complete and properly notated full orchestral score which can be played by a large orchestra, and which will sound great on the first pass. There are too many to list them all here, but these are a few considerations, which hopefully won’t sound too technical: proper string voicings (taking tracks played by an ensemble patch, and rendering them properly for the ensemble at hand, with violins, violas, cellos, and basses, dealing with divisi passages, etc.); wind and brass voicings that use the available ensemble to best advantage; adding all necessary dynamic markings, slurs, and articulations; dealing with duplicate tracks from the MIDI file (for example, the same notes played with different articulations to get a bigger sound on the demo), and figuring out how best to render those with the ensemble at hand; smoothing out transitions between sections which may have been edited during the revision process… And this is to say nothing of aleatoric passages and effects which may be included on the demo — that’s too complicated to discuss here, but rendering such music effectively can be a challenging part of the job. All of this requires a detailed knowledge of how orchestral scores ought to look on the page, in order to quickly get the desired sonic results, when performed in the recording studio by the musicians.

It also should be mentioned that in many contemporary film scores, there are numerous electronic or other elements in addition to the orchestral elements, though generally the orchestrator is only responsible for the orchestral elements. But one must be aware of these other elements, and have a sense of how they will likely be combined with the orchestral tracks. What is common between the role of the orchestrator in earlier eras and now is that the orchestrator’s job is to help execute the composer’s vision for his music, at the highest level possible. For me, when I am on the orchestration team of some of the most talented and successful film composers working today, I consider this to be a pleasure, a challenge, and a privilege. Finally, as for the question of orchestrators serving as ghostwriters: to my knowledge, sometimes in the industry this does happen, although I can tell you that this has never been the case with my own work. For all of the composers for whom I have orchestrated, I have done just that: orchestrated existing music, not composed it.

You have orchestrated for several A-list Hollywood composers. How do you explain your success?

It’s important to note that for the most part, my work as an orchestrator has been with composers who have existing relationships with a lead orchestrator on their team, and so my interactions have been primarily with those lead orchestrators. In the case of Michael Giacchino, his lead orchestrator is Tim Simonec; for James Newton Howard, it’s Pete Anthony; and for Thomas Newman, it’s J.A.C. Redford (who was also the lead orchestrator for the late James Horner). These are three important examples among my orchestration work, although there are others also. My respect and admiration extends not only to these A-list composers, but to each of these A-list orchestrators with whom they have longstanding relationships. I have learned so much from each of them, and I consider them to be both valued colleagues and friends.It’s also important not to overstate my role as orchestrator on any of these projects; I have been one member of these orchestration teams, and have not orchestrated too large a percentage of the score for any of these films on which I’ve worked.

As to whatever success I may have had as an orchestrator: I think that part of the answer must lie in a willingness and ability on my part to adapt to each team’s situation and workflow, by carefully observing the process in which I’m invited to be a part. Having knowledge of standard orchestral repertoire, through my years of exposure to and study of it, certainly helps. Having familiarity with different softwares, and being able to work equally well in Finale or Sibelius, is advantageous. And I think that being enthusiastic, fast, accurate, and most of all, reliable is very important!

Did you do some orchestration work, on film scores or other projects, for which the composers did not provide you these detailed orchestral demos? If so, does that gives you more freedom?

Though it’s less common in contemporary orchestration work, the answer is yes. I have had opportunities to be part of orchestration teams for both Alan Menken and Maury Yeston, two more composers whose work I greatly admire and respect. For Alan Menken, this was a film score; for Maury Yeston, it was a ballet. In both cases, what the composers provided was a piano score (in the case of Alan Menken, two or three piano tracks, with MIDI data). The music was certainly complete in terms of melody, harmony, counterpoint, etc., but instructions for instrumentation were minimal. These were actually very rewarding projects on which to work, because they demanded a more traditional or old-fashioned approach to the orchestration, which allowed for some creativity in the execution. So there are different ways of working, but all valid, and all can be rewarding.

You orchestrated for Horner on The Amazing Spider-Man and Living In The Age of Airplanes, where he blended orchestral elements with electronics. Was it a particular challenge?

Of course, it was a great honor to have the opportunity to orchestrate for James Horner, who was so beloved, and is deeply missed by so many. In both of the cases you mentioned, while the score did blend orchestral and electronic elements, as an orchestrator, I dealt only with the orchestral elements. I should mention that for these projects, I did not interact with James Horner himself, but with members of his music team: J.A.C. Redford, his lead orchestrator, and Simon Franglen, his electronic music programmer and arranger, both superb musicians. As you know, Simon Franglen completed the score for The Magnificent Seven, based on themes that Horner had composed shortly before his death. I think that Simon did a remarkable job with this, under very challenging circumstances.

You orchestrated some of John Williams’ iconic music from Jurassic Park for Jurassic World, scored by Michael Giacchino. Did you have access to the original manuscript?

Yes, I orchestrated only one cue for this film, and it turned out to be John Williams’ iconic Jurassic Park theme, adapted by Michael Giacchino, used right near the beginning of Jurassic World. What can I say? This was an absolute joy and privilege to do! I’m grateful to have been given this opportunity. I did not have access to the manuscript, though this cue did reference the published score in the John Williams Signature Edition. One can learn something from every bar of John Williams, of course, and it was cool to see what Michael did with this, and how it was used in the film. Very fun.

You recently orchestrated for JNH’s Fantastic Beasts And Where To Find Them…

Yes, I was really delighted to be part of James Newton Howard’s orchestration team again for such a high-profile and greatly anticipated movie. Though I don’t think I should say anything about the specific musical content before the release, I can tell you that the music on which I worked is truly exciting and first-rate. I believe that JNH has composed another marvelous score, and I am among the many who are looking forward to seeing this one when it’s released!

Recently, you recorded in Hollywood an album with orchestra and choir, recorded and mixed by Tommy Vicari. Can you tell us more about this music and this recording?

What I recorded was a group of cinematic demo cues in a variety of styles — not concert music, and not a full-length album: about 16 minutes of material. Essentially, after having devoted most of my energies over a number of years to composing concert music, and orchestrating film music for other composers, I decided that I wanted to record some material with many of Hollywood’s finest players, to demonstrate my capabilities composing cinematic music. At this point, though I’ve worked on many exciting projects as a composer, orchestrator, and conductor, and my concert music is heard widely, I’ve not yet had the opportunity to compose a feature film score myself. Though I put that goal aside for a number of years to focus on these other aspects of my career, I decided that this remains something which I’d like to do, and that I needed a first-class recording of specifically cinematic music to help with this pursuit.

So after spending some time composing these cues, I worked with top Hollywood contractor Peter Rotter, who engaged a 74-piece orchestra of A-list players, and vocal contractor Jasper Randall, who engaged a marvelous choir of session singers. We arranged to record this on the wonderful Sony (formerly MGM) Scoring Stage, which of course is where countless classic film scores have been recorded, and where John Williams often records. I have admired Tommy Vicari’s work on so many of Thomas Newman’s scores over the years, so I was delighted that he agreed to record and mix this for me, and he did a great job. And Patricia Sullivan at Bernie Grundman Mastering applied the finishing touches to the tracks. I think they turned out very well, and it was especially rewarding to work with these superb Hollywood musicians, many of whom are colleagues and friends of mine. So this was a significant career investment, and a joy to do. There are videos from the sessions on my website, YouTube, etc…(used here as musical examples throughout the interview – ED).

You conducted some performances for Josh Groban. What was that experience like?

The gig conducting for Josh Groban was completely unexpected and great fun to do! Years ago when I was a young guest conductor at The Henry Mancini Institute, I met Sean O’Loughlin, who has gone on to great success as a composer, arranger, and conductor for various popular music artists. He has been Josh Groban’s tour conductor for a few years. Sean and I reconnected at the Hollywood Bowl last year, when my Silver Fanfare opened a concert at the Hollywood Bowl featuring Journey, for which Sean did the orchestral arrangements. Josh Groban became ill and had to reschedule some tour dates in Texas, and Sean was unavailable for those, so he asked me to fill in for him. I had to learn all the charts for Josh’s show for just three performances, but I was very happy to do that. It was a terrific experience. That man can sing!

Can you tell us something about your upcoming projects? And are there some types of composing projects that you have not done thus far, which you’d like to do?

I’m very excited that in April 2017, the Pacific Symphony in Orange County, California, one of America’s best and fastest-rising orchestras, led by conductor Carl St.Clair, has programmed my work Ellis Island: The Dream Of America as the centerpiece of their annual American Composers Festival, alongside the music of John Adams. Since this festival began in 2000, it has featured the music of many of the finest American composers from the worlds of both concert music and film music: Copland, Bolcom, Glass, Daugherty, Danielpour, Harrison, Ellington, Previn, James Newton Howard, Williams, Shore, Horner, and Goldenthal are among the composers who have been featured. So to be included in this group is of course an enormous honor for me, and I’m looking forward to the activities I’ll be doing in conjunction with this festival.

Presently I’m in discussions with a major American orchestra about a commissioning project for the fall of 2017, which would be quite exciting. I can’t speak about that yet, but please stay tuned. I’ve also accepted my first-ever commission for a wind ensemble/concert band work, for The American Band, for their 180th anniversary in 2017. This is new musical territory for me, so it’s interesting to do. There is also some more orchestration work on the horizon. As to new types of projects, as I mentioned, I’m now on the lookout for film scoring opportunities of my own, and we’ll see what may emerge. Recently I’ve also begun to think seriously about the prospect of composing an orchestral ballet score, and have begun reaching out to choreographers at major American ballet companies, in an effort to make connections in that field. I’ve never worked in the ballet world, but a number of people have suggested to me that is something for which I may be well suited, and I think that would be a rewarding type of project as a composer.

More information about Peter Boyer and his work may be found at PropulsiveMusic.com

Interview conducted on October 2016 by Olivier Soudé

Transcription : Olivier Soudé

Pictures : © Danika Singfield (portrait), Benjamin Ealovega (Abbey Road) & Ricky Chavez (Sony)