![]() CLIQUEZ ICI POUR LIRE LA TRADUCTION FRANÇAISE

CLIQUEZ ICI POUR LIRE LA TRADUCTION FRANÇAISE

Eleven hours of score for the quest for the Ring

Ninety themes to illustrate Middle-Earth

One book to discover them all

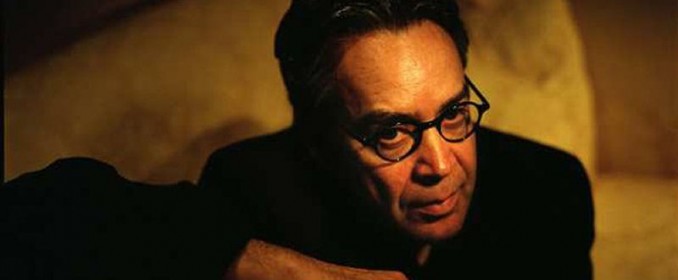

One of the biggest cinematographic hits of the beginning of the 21st century, The Lord Of The Rings films gave to Canadian composer Howard Shore the opportunity to compose the work of a lifetime, a piece that will probably stay forever as his best. When he was officially announced as the composer of the trilogy, there were many reactions, but only a few to defend this choice. Nevertheless, with the Peter Jackson films, Shore fulfilled his duty beyond our greatest hopes. As the three volumes of The Lord Of The Rings were conceived by Tolkien as a whole, the three scores have been thought as one, patiently built by Shore from The Fellowship Of The Ring to The Two Towers and finally The Return Of The King.

Doug Adams, the American musicologist author of The Music Of The Lord Of The Rings Films, was able to go deep inside the musical odyssey of Howard Shore as the composer invited Adams in 2001 to follow him into Middle-Earth. The Music Of The Lord Of The Rings Films take us inside the numerous musical themes and motifs, dealing about their use into the three movies, introducing choir and songs texts, reporting about the scoring sessions, the special instruments used within the scores… Rich and sharp, beautifully presented, The Music Of The Lord Of The Rings Films proves that beyond the own beauty of the music, Shore’s work is distinguished by its profoundness and intelligence, as much as Tolkien’s work is. During the following interview, we talked with Doug Adams about his work and his choices for The Music Of The Lord Of The Rings Films.

We know you for your work with Film Score Monthly. What was your background before that?

I was born in the 1970s, so film music was a big part of my formative years. The Empire Strikes Back was probably about the third or fourth film I ever saw in the theater. I was absolutely rabid about it – couldn’t get enough. So my dad went out to buy me the LP of The Story Of The Empire Strikes Back, which essentially contained some dialogue from the film, a narrator, some sound effects and music, and took you through the basic plot. This was before the days of VHS, so that’s how you would revisit a film. However, my dad accidentally brought home John Williams’ original score album. I played it anyway, and after a few minutes was enthralled. I could hear the whole story in the music. It was so colorful, so evocative. I’d never heard anything like it. When my dad realized he’d brought me the wrong LP, he offered to take it back an exchange it, but I wouldn’t let him.

I think I was already taking piano lessons at that point, but I started to take music much more seriously then. I don’t know that it was necessarily connected to the LP, but it was definitely around that time. I devoured everything I could get my hands on. My parents had taken a little music appreciation in college, so they pointed me toward Beethoven, Rimsky-Korsakov, Bizet, Prokofiev, and so on. At the same time, I started to develop a taste for somewhat edgier composers, Bartók, Varèse, and Stravinsky in particular. I had a Zubin Metha recording of Le Sacre du Printemps that I just about wore down to a nub. I also fell in love with 1940s jazz, mostly bebop. I loved the thick chord extensions and the jagged rhythms. I had a friend who played saxophone who’d somehow stumbled into a Charlie Parker Real Book, so we spent a lot of time digging up old recordings and translating them into really awful duets for sax and drums. I can remember being about twelve years old and rummaging through record stores on college campuses trying to find John Coltrane albums. I got some funny looks.

I also started studying percussion very seriously, and was eventually accepted into music school as a percussion student. From there I went on to graduate school where I completed a Masters in music composition. But I never gave up my love for film music. At the same time I was studying Pergolesi and Bach in college, I was also teaching myself about Korngold and Herrmann. I made a point to seek out music by Takemitsu and Ifukube to perform on recitals. I played percussion on a recording of Broughton’s Tuba Concerto. I think I even did an arrangement of Williams Cantina Band for a steel drum band that I played with. I always thought of film music as every bit the equal of that which my professors were having me study, so I made a point to set them side-by-side as often as possible.

Somewhere during those college years, I became familiar with Film Score Monthly. I think I tracked down Lukas Kendall on Usenet and dropped him a line to see if he’d let me try writing an article for him. He essentially said « Sure, do a retrospective piece on Young Sherlock Holmes » and sent me Bruce Broughton’s phone number. I was terrified to make the call. You know, I was just sitting in a noisy dorm room with a sign on the door: « Please be quiet, I’m on an important phone call. » But the piece came out OK, so Lukas asked me to do more. Eventually I was doing a piece or two for just about every magazine. I think I was always more interested in the composers than in the records or the business. I always wanted to know exactly how they came up with their ideas, I wanted to understand what they were doing compositionally, and I wanted others to understand. That was always my angle.

Apart from Howard Shore, who is your favorite composer?

I’ve always felt that Igor Stravinsky was the epitome of the modern musician. He embraced everything that was around him, and he accepted both change that he initiated and change that was forced upon him. I wish I’d met him, but he died before I was born.

So it is because of your collaboration with FSM that you met Howard Shore?

Yes, unquestionably. Howard and I first spoke for an FSM interview covering his work on Cop Land in 1997. And we were doing an interview on The Score in 2001 when he invited me to be a part of The Lord Of The Rings.

Do you remember the first movie you saw scored by Howard Shore?

I saw The Fly when I was about eleven or twelve years old. I was at a friend’s house for a party and it was on TV. Absolutely frightened the life out of me!

What was your knowledge of J.R.R. Tolkien’s universe before the announcement of the movie adaptation by Peter Jackson? Were you then a die-hard fan of Tolkien?

I was not a neophyte, but I was far from an expert. I was a fan, unquestionably, but I appreciated Tolkien’s work on more of a surface level. Of course, I was pretty young when I was first exposed to it all. When I began speaking with Howard Shore about his early work on the films, I noted that everyone on this project used proper names. No one said, « Oh, we’re working on Act Two where Elijah and Sean are together in a cave« , they said, « We’re working on Moria where Sam and Frodo are in Balin’s tomb. » It was all very specific. So I decided I needed to re-familiarize myself with Tolkien’s work, and this was when I started to really think about the connections in his world, and its place as a modern myth.

Before The Lord Of The Rings, Shore was seen as a « cerebral » composer. When he was chosen for the trilogy, do you remember the overall reactions over his assignment?

Most people expected the project to go to someone like James Horner or Basil Poledouris, both of whom were interested in the project, though neither was actually considered by the filmmakers. However fans were assuming the film would go to someone who was primarily known for that sort of lush, genre music. I don’t mean that as a pejorative. Howard, however, was known for smart, thoughtful scoring that was deeply felt. He was edgier. He specialized in creating entire worlds out of sound. He’d also worked on a number of successful literary adaptations. In retrospect, it makes perfect sense, but everyone was caught by surprise at the time.

How did he get the job?

Fran Walsh actually tells the story of how Howard was selected in the book’s Introduction. In short, the filmmakers found themselves using Shore’s music again and again when assembling a temp music track for their animated storyboards. Howard’s music was so successful in expressing the emotional pitch of this story that they offered the job to him.

How did you succeed to go from FSM to the musical universe of The Lord Of The Rings films?

For me, FSM was the perfect proving ground for the kind of musical writing I was interested in. I’d always tried to find a way to write about music as its composer saw it. So much writing on music is rooted in subjective expressions. And that’s great, that’s valid, but by itself it’s only part of the picture. Too often writers are afraid to say something specific because they themselves don’t understand the technicalities of music, or if they do, they’re worried that they’ll frighten off their audience. But there’s a real beauty in a composer’s thinking. And if you can find a way to express that beauty, and make the technical aspects perfectly clear even to non-musicians, you can create something that can bring the music come alive in an entirely new way.

The beauty of film music – or any narrative music – is not that it’s just a collection of moods, but that it’s a collection of moods in service of a story. After all, what are moods without context? So if you can appreciate how music tells its story – and on a truly musical level – then you can understand how it exists in the eyes of its creator. I’m not trying to sound theological, of course, but there’s something wonderfully pure about seeing a piece as it was envisioned. The thing is, a non-musician can understand this perfectly well. If a writer thinks hard enough, these types of ‘technical’ discussions can transcend their origins and become expressive in their own right. FSM provided me ample opportunity to experiment with these ideas. Obviously, some pieces lent themselves to this better than others. But I always wanted to bridge that gap between music, its audience, and its creator. And this is exactly what I ended up trying to do with The Music Of The Lord Of The Rings Films. I thought that if I could deeply understand Howard Shore’s concept of this music, and if I were allowed a palette large enough, I could bring the audience into the score in an entirely new way. Howard provided me such incredible access, it was just thrilling. He’s such a brilliant composer, and there’s such deep thought and feeling behind everything he does.

Can you describe your job following Howard Shore into Middle-Earth?

It was never a « job, » per se. I wasn’t hired. The whole project began as a friendly invitation from Howard. He basically said, « This project looks like it’s going to be pretty special. Would you like to stick around and see what it’s like? » I visited him at his office several times and we got on very well. We have very similar interests and temperaments. So I gradually earned his trust, and since Howard is so well respected, that eventually translated into trust from the studios and the filmmakers, and eventually they just allowed me access to everything. We honestly did not know from the outset that this would turn into a book. In fact, we didn’t really have any idea what we were working toward. But we had faith in the power of Tolkien’s creation, and knew we’d find our path. Howard had my name added to a preview screening of The Two Towers about a month before it hit theaters. And I’d had the CD of his score for maybe a month before that.

When I returned from that screening, I think I suddenly understood what Howard was creating. I loved The Fellowship Of The Ring dearly, but I don’t think I’d fully wrapped my head around Howard’s vision yet. He’d told me where he was headed, of course, but The Two Towers was the epiphanic moment. I came home from that, took out all my research from The Fellowship Of The Ring, added my first impressions from The Two Towers, and typed everything up into a very, very early version of the book. On my next visit to New York, I sheepishly gave Howard what I had, and the next day he brought it back, marked up here and there in red pen, just like a professor. But he’d read the whole thing start to finish, and was very enthusiastic. He loved the idea, and wanted to pursue the project. A few months later I found myself in London at the recording sessions for The Return Of The King, and everyone there had a copy of this silly little document I’d printed on my home computer. The awful screencap graphics I’d stuck in place were still there, even! The producers had this, Peter Jackson had one. There were copies sitting around Abbey Road.

Did you witness any part of the composing process?

I was present for a few of Howard’s meetings with the filmmakers, and you’ll see in the book how he worked with Peter Jackson and how those meetings directly translated into his musical ideas. But you also have to give creative people the space they need in order to create. So it wasn’t like I was sitting in the corner watching Howard drag the pencil over the paper. Composition is a very personal process, and it should never be disturbed in that way.

Howard Shore is known for composing and orchestrating his own scores, which is something usual here in Europe but not the usual case in hollywood. Did the studio try to impose orchestrators?

Howard was working with wonderful producers, Pal Broucek and Rick Porras in particular, so he had great support for his vision. No ugly studio politics here, thankfully.

Once the decision to write the book was made, how much time did you think you would need?

We began into the Complete Recordings shortly after The Return Of The King. The original idea was to release all three boxed sets in a single year, but we learned that the job was far more demanding than we’d imagined. We always imagined we’d attack the book when the boxed sets were done, but that project ended up taking three years. And then the book itself took a few years. So we learned as we went. At the time of the release of the Complete Recordings, you wrote the liner notes and in addition, free to download, sharp and detailed notes on each score. How much time did you spend on those works? Were the Annotated Scores a way to promote the book you had in mind or was it a different engagement? I was working on the liners and the Annotated Scores as the boxed sets were being produced, so the two were really developed hand-in-hand. We all worked together sending our review notes and trying to fit all these components together and create a beautiful final piece. We usually began work in the late fall/early winter, and would conclude with the Annotated Score layout in September or October. So it was like an eight or nine month work cycle. And by the time we finished with reviews and edits, maybe closer to ten or ten-and-a-half months. By the time one would hit the shelves, we’d begin into the next. Everyone would get a nice congratulatory email one week, and a day or two later we’d be listening to masters for the next one.

Who was the captain on board? What kind of artistic freedom did you get on the book content?

The real heart of the book’s creative team consisted of Howard, Alan Frey (Howard’s assistant who also supervises content on many projects), Gary Day-Ellison (our layout artist), and me. In terms of content, Howard gave me incredible freedom, but of course, this was all following years and years of discussion so that I could see the music through his eyes. I think that he trusted that we shared a vision, and he let me express that. The production itself was more collaborative, because we wanted to make something exceptionally beautiful. We didn’t want something dryly academic. The Lord Of The Rings is such a passionate story, and Howard’s music is incredibly beautiful. The book needed to have that kind of beauty as well.

When did you create your own blog and why did you do it?

During the Complete Recordings, I spent a lot of time answering questions on various message boards. When the attention switched to the book in late 2007, it simply seemed easier to answer these questions in one place. I stated the blog for that purpose. People seemed to respond, so I kind of kept everyone in the loop as my work progressed.

The release of the book was delayed because of the upcoming production of The Hobbit. Was the book already finished, or did you take advantage of this delay?

We were ready to release the book in the fall of 2009, but there the studio and the estate had to work through some business of their own, so we delayed the release in order to stay in the clear. It ended up being a terrifically advantageous situation for us, because we were able to redesign the book in a much more beautiful way. Gary joined our team, and John Howe and Alan Lee allowed us access to their artwork. We ended up with something much more impressive. It was terrifically upsetting to me at the time, of course, but some things are simply meant to be, I think.

The content of the book is much more than the liners notes from the Complete Recordings and the Annotated Scores… What did you wish to add exactly?

The content from the liners and the Annotated Scores is all in the book, but expanded and more fleshed out. We always thought of those as previews of the book’s content. The Complete Recordings demanded that we look at one score at a time, so the content was presented in segments. The book, however, puts all the pieces in place, and shows you the whole story at once, so you get a much better sense of Howard’s vision of Middle-Earth. And of course, we’ll show you more themes and connections to help you get that comprehensive view. At the same time, the book delves more into the creation of these scores. It explains how certain decisions were made, and what the recording sessions were like. You get a chance to meet some of the orchestra members. This creation is a story in itself, so the book opens and closes with this type of material. We begin the book in the real world, then divert to Middle-Earth for a few hundred pages, and finally return to the real world. I like to think of it as a narrative analysis. It’s its own type of storytelling.

What can you tell about your work with your editor, Carpentier And Alfred Music Publishing?

Paul Broucek, the music producer on the Lord Of The Rings films, and now head of music at Warner Brothers, brought the book to Alfred Publishing, which, at the time, had recently acquired Warner Brothers’ publishing division. I met with Alfred both in Chicago and Los Angeles, and did a basic pitch meeting wherein I explained my ideas. More than anything, I think we just wanted to meet each other. Alfred also had a pre-existing relationship with the people at Carpentier, so the team-up seemed like a good move. Both companies had experience in different sectors of the music world. Both companies have shown incredible support for this book, and I think we’re all incredibly appreciative of that. It’s really a unique project. I don’t think anything quite like this has ever been attempted. So it’s wonderful to work with companies that understand that vision and support it. Joe Augustine, in particular, has worked tirelessly behind the scenes keeping the two companies in sync. He’s been spectacular to work with.

You hired a designer for the book. What can you say of the work of Day-Ellison Associate?

Gary worked tirelessly on this project. He was the only one of us who had worked on books before, so he was an incredible guide into that world. The book has many sections, but at the same time we want it to be read straight through. It’s not a reference book. Gary showed us how to set up specific visual languages so that the eye can be guided through the book. Visually, you should always know where you are. So Gary created a design where you could open to any page of the book and know what you’re seeing, be it the discussion of a theme, a full composition, a choral text, or a behind-the-scenes story. He really taught us how to establish that hierarchy. He also brought John Howe and Alan Lee on board, and found a way to properly present hundreds of their sketches – many of which have never been seen before. It’s such a beautiful book now, and that’s all due to Gary. Every page is so carefully designed, and it’s a fairly long book! It feels like an antique storybook in a lot of ways, so it has that narrative flow we always wanted.

The cover is a stunning original drawing from no one else than world famous artist Alan Lee…

The cover was one of the last things we approached. We tried nearly three-dozen variations, I think. As we closed in on a design, we knew we wanted to meet two criteria: the design should represent a major musical moment from the story, and it should focus on a heroic or positive moment. We had a sketch of the Eagles that met both of these criteria, but it was part of a larger sketch. We tried cropping it and enlarging it, but we felt we lost something doing that. One day Alan Lee simply sent over a short, polite email stating, « I can draw you some more Eagles. Give me a day or two. » He’s such a gentleman. Very soft-spoken and kind. And of course, the final cover is gorgeous. We’re so proud to have it. I should also mention that John Howe was equally kind and supportive throughout the process. He’d be constantly sending us pieces from New Zealand when he had break in his design work for The Hobbit. Both John and Alan’s work compliments the other’s so well. They’re a great team, they bring such a balance.

Who took the decision to add an audio recording belong the book?

Howard and I had been working our way through The Rarities for a few years, and it was he who first suggested that they should be included with the book. It’s such an honor, really.

You talked about a possible Audio-DVD to present The Rarities. Why did you change for a CD?

We considered a number of options before we actually finished sorting through Shore’s archives. But we always knew that, in the end, the material would dictate the media. When we finally sat down to assemble The Rarities, we found that we had exactly enough material to fill up a single compact disc. It would be extremely full, but it would fit perfectly. To be clear, Howard and I didn’t change our minds, we simply kept our creative process very open and let people know what we were thinking and doing. A huge project like this involves a number of creative decisions, and in this case, the world got to see them as they occurred. It’s always important to let the material dictate the project. If you do it the other way around, you end up making crass commercial decisions, and we didn’t want to do that. We wanted to make the best project we good, and to maintain our aesthetic vision. That’s not easy to do, but if you keep your ears open, you’ll always find yourself pushed in the right direction. You just have to remember to maintain artistic aspirations, not business aspirations.

How did you select the content of the audio CD?

The Lord Of The Rings films actually recorded more audio than just about any film project in history. At one point there was an entire storage unit at Abbey Road dedicated solely to the trilogy sessions. All in all, there’s more than a month’s worth of continuous audio. Now mind you, a lot of that is repetitive material, or flubs, or what have you. I spent about a year-and-a-half going through Howard’s archives to make sure we had everything in the Rarities Archive. It was a big project! He and I went through all the discoveries and assembled a program for the disc that would present all our findings both as an archive of unused material and as an album that could be enjoyed straight through. It needed to have that same structure as the book, something that was informative, but expressive in its own right. We, of course, did not want to repeat material that was previously available, but it really wasn’t an option anyway. It wasn’t an option because we set out to ensure we didn’t ask anyone to pay for the same material twice and the new unused material essentially filled the disc. It was a pretty serendipitous circumstance, really. Logistics and aspirations coincided nicely.

Part of the Rarities CD presents demo mocks-up…

These mock-ups were prepared on a Synclavier, a very sophisticated sampling computer. Greg LaPorta, who specializes in this sort of musical technology, prepared them for the original film productions. In addition to being expertly executed, the mock-ups illustrate very early versions of major themes, so there’s often a good bit of unique musical content contained within them: the Shire theme had a very different B-phrase, the Ent music included some unusual percussion writing, the Gondor theme was harmonized almost entirely with major chords… And while this music is quite expressive in its own right, it also illustrates Shore’s creative process and highlights how he shaped this now-famous music. As I say, we had twin goals with the Rarities album – it needed to be both beautiful and illustrative.

The book is available worldwide. Do you already know if it will be translated in other languages?

This is something we’d like to do eventually, yes. It takes deals a little while to fall into place, of course, so we’ll say how everything plays out. But it would be great to pursue.

What are your hopes in term of sales? Are you already aware about the worldwide pre-orders?

Well, I hope it sells! This being my first book, I have very little frame of reference in terms of what good numbers are. But my goal really is to reach people and show them something about this wonderful music. I’ll let the business people – who are very, very bright, and very attuned to such things – worry about numbers.

What will be your professional future?

I think there will probably be some more books – and probably some trips out of Middle-Earth. And yes, we’d be very interested in doing this all over again for The Hobbit pictures. No official announcements yet, but the road goes ever on, of course!

What’s your feedback on the whole experience – almost a decade long – with Howard Shore? He received many prizes around the world. What’s the secret behind this incredible success?

If there is any secret to the success of The Lord Of The Rings music, it is perhaps related to the sincerity with which the music was created. Howard Shore set out not to create something commercial, not to sell a product, but to express something directly from his heart. And the filmmakers understood this, and supported it. I think everyone involved with this project knew it would eventually become their legacy, and they simply poured themselves into it. As they say, there is only one Lord Of The Rings !

Interview conducted in August and September 2010 by Olivier Soudé

Adaptation : Olivier Soudé

Pictures : © New Line Cinema