One of UK’s most celebrated composers, Debbie Wiseman was born in London, where she studied piano and composition at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. Her film music credits include Tom And Viv, Haunted, Wilde, Lighthouse, Tom’s Midnight Garden, Arsène Lupin, Flood and Lesbian Vampire Killers. Amongst her many television music credits are Father Brown, Judge John Deed and more recently A Poet In New York and Wolf Hall. Wilde Stories, her album of music to accompany the fairy stories of Oscar Wilde, was nominated for a Grammy Award. In 2008 she also composed and conducted the Different Voices album with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, with narration by Stephen Fry and lyrics written by Don Black. She also appears frequently in concert halls across UK conducting her film scores. We met last year in Cordoba during the International Film Music Festival, where she kindly agreed to answer to our questions…

You don’t come from a musical environment. What led you to music as a child?

There was no music in my family. My parents didn’t play an instrument or even learn to play, but they loved music. I went on a family holiday, and there was a piano in the dining room at the family hotel. I was about 6 or 7, and I went to the piano, and I was just fascinated by it. I loved the feel of it, and the look of it… You know how kids sometimes go to a piano, use it as a percussion instrument and bang it? But I went to it thinking: this is beautiful, I want to learn it. The idea of writing a melody and getting involved in music came from that. And after this encounter, I said to my parents that I’d love to learn to play the piano, and that was the start. And then I became almost obsessed with it. When I was at school, taking piano lessons and starting learning the repertoire, learning about scales and harmony, it became a concrete idea. This is what I love: I love music, I love writing, I love being around music and making music. I was just happy to sit at the piano. I enjoyed lessons, I liked learning English and Math, some French… But music was always more important. I think I could have given up any other subject at school, like science or physics or whatever, I would have done it happily. But if somebody had told me to give up my piano lessons, I would have been destroyed.

You studied with composer Buxton Orr. What was his main teaching?

The main thing I learned from him was simply how to compose, to be able to structure melody, to be able to orchestrate. He was very big on orchestration, so he always taught me that when you write a melody, you must decide which instruments are going to play it. Is it going to be on a flute, on a horn, a violin? So as you write, you think of the orchestration, and those come hand in hand, it’s exactly the same part of the composition process. That stuck with me. He was very strict about putting everything on the page for the musicians. So when you write a melody line, you don’t just write the notes, you write the phrasing, and the dynamics and the shape of how it should be performed. It’s very important. So now, when I give a musician my music, it is very well accented, the dynamics are there, it’s absolutely as it should be in my head. And then, obviously, they get to the music and they interpret it and make it their own, which is wonderful, but they know very well from looking at the page of music how it should be played.

But sometimes, you must transpose a melody from one instrument to another. How do you handle that?

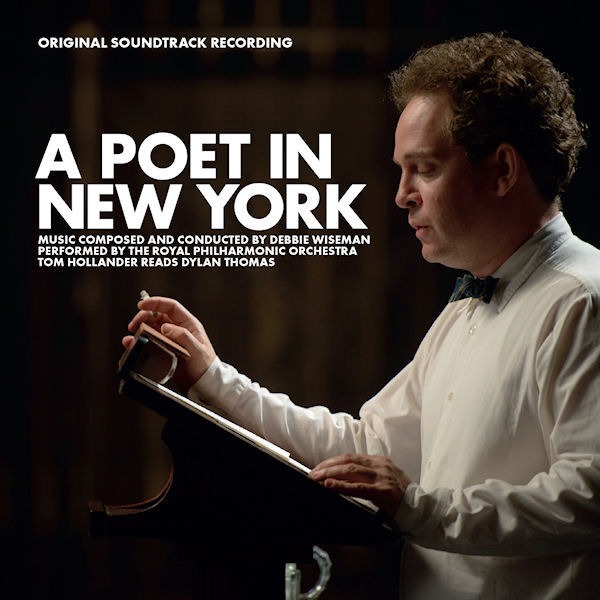

When you are writing for a film, you orchestrate to suit the film. For example, in A Poet In New York, the main theme is played on an acoustic guitar. But when you hear it in concert, the main theme is played on the violin. That’s a practical thing, because to have an acoustic guitar in this sort of environment can be difficult, you have to mike it up… It sounds different, of course, since it’s on the violin, but I just had to think about how the violin would play this, how the guitar would play this. It is the same theme, but you just have to think it in a slightly different way. And Buxton also encouraged me to play an instrument, play a scale on each instrument of the orchestra. So you know how it feels, and when you write for it, you have a kind of understanding of what that instrument is. He really felt it was important to really understand all the instruments of the orchestra before you start writing for them. And I think it is a good lesson because when you are writing for these instruments, you feel much more confident if you know how they sound, and how they should sound, how they play and how they sound best. It’s no good writing a melody which is impossible for a violinist to play because it’s too high or too low for the instrument, or impractical for it to play. So he taught me to write for the instruments where they sound best, so they really shine and you can let the melody speak.

You experimented with all different parts of the orchestra?

Yes, when I was starting, I did. Now, because I understand the orchestra much better than when I was a student, I have an instinct to know. I look at a film and I think « I want to write this for a solo clarinet » or whatever. There’s a slightly more immediate reaction.

You have a special relationship with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra?

I have been working with them for quite a few years. I love the orchestra and the way they play, their unity. I like the string section very much. So they became my favorite orchestra for many projects. But I choose the musicians always for the best of the project, so sometimes they are very suitable because I might have something that requires a lot of strings and I know their strings are fantastic and they might just be perfect for it. Other times, for example on Wolf Hall, it’s a Tudor story, so it’s going to be early instruments, maybe late 15th century, early 16th. That wouldn’t be suitable for them, I need a lot of specialist musicians that I handpick. And if I need a string quintet, I choose the musicians individually. It just depends of the project: you may go with the orchestra, individual musicians or ensemble.

Do you feel close to one or several classical composers?

Funnily enough, when I was starting, I listened a lot of the French composer Olivier Messiaen, and I absolutely loved that music, because of the color, it’s so bold and exciting, and very different from the music I was writing. I love Messiaen, I could listen to that music all day, particularly the Turangalîla-Symphony which is one of the first pieces I heard of his. I love Mozart because of the melodies, Ravel, Debussy… a lot of French composers actually. I also love Beethoven, Haydn… Not one as a particular favorite, but just a huge array of classical composers.

You said you chose to work for pictures because it’s the natural place to write melodic music…

Music performed in a concert hall is more experimental, more avant-garde and more atonal. I like writing melodies, so the natural home is film and television, because you are encouraged to write themes, to give characters themes. Directors often come to me and say: « I really want a strong melody for my show, I want this to be memorable. » And that is a gift to me because this is what I love doing, writing melodies. So it’s a natural partnership.

In the 90’s, you provided a piece for the unveiling of a portrait of Margaret Thatcher…

That was when I was studying at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. I was a composition student, and one of the teachers told me that we had been asked by the office of Margaret Thatcher that they would like a student to compose a piece for the unveiling of the portrait at the Carlton Club in London. I couldn’t believe it! I wrote a piece that was about a 3 or 4 minutes, quite grand, as you may imagine for the unveiling of a portrait, and I conducted the piece there. She was there, she came down the steps and thanked me, shook my hand. She was lovely and I gave her a copy of the score. Can you imagine? As a student, that was so exciting!

In your early career, you composed for a lot of documentaries. At that time, were you ever afraid of being typecasted?

Absolutely! At the beginning, of course, because I had written a lot of these, and people think that because you are writing for documentaries, you will never be able to do dramas or films. But in the end, it was music to me. I was still writing music, and I thought it was better to keep busy and write music, to be commissioned to write music for a documentary, rather than to just sit home and not do anything. It was a very important part of the process, and also a learning experience in terms of working with the musicians. Some of the documentaries I worked on had a reasonable amount of musicians, and some others had a small ensemble of 10 or 15 musicians, but I was still working with them and learning how to orchestrate, so it was important.

How did you get involved with the music for the Diaspora Museum in Tel-Aviv?

That was a very different project. A producer I had worked with on a documentary recommended me to the people who were in charge of the organization in the museum. They asked to write the music. So when you enter the museum, there is a 20 minutes film about the history of the Jews, and my music runs through the whole 20 minutes. It starts quite small, and then builds as it tells the story. It was a fascinating project. Unfortunately, I never had the opportunity or time to go and visit the museum. But lots of my friends have seen it and told me it is nice…

What is your typical day at work?

There is not a typical day. But if I’m on a project which is demanding, I start very early in the morning, around 6 o’clock, and I work until lunch, and then I carry on. But I try to work not too late into the night because I find it quite hard to get to sleep. So if I can, I try to stop at about 8 or 9 at night, earlier if I can. But I like early mornings to write. It’s quiet, the phone doesn’t ring as much, it’s peaceful, and you’re fresh, I like that.

How much time do you spend on composing on the piano, and how much time doing mockups?

I work at the piano to shape every single music cue. My first stop is the piano, and I write everything down on manuscript paper. I score it, I get the theme, I get harmony and then I orchestrate it and do the mockups for the director. And this process takes quite some time because I have to play everything in, play the flute, the oboe, the horns, the brass, percussions… I would say it is about 50/50 piano and mockups.

How much music do you compose each day?

Honestly, I don’t know. It is definitely more than 3 minutes, but I don’t give myself a time limit. I just write as much as I physically feel I can in a day, depending on the project, what I need to get done. If it’s not that important that I finish a particular sequence that day and that I need more time, then I take the time. But I write as much as I can. I know I had enough when I get tired.

What do you think of television music, compared to film music?

Television is definitely joining film. Fantastic directors work in television now, directors that maybe would have considered doing films, but now are thinking of television as a fantastic way to start their career. I love working very fast. And the fact that it’s fast means that you’re very concentrated. Sometimes the music for an episode will be composed, orchestrated and recorded within three weeks. So it’s a tiny space of time. And then you’re on episode two, episode three, and it’s another three weeks. I’m just working on 15 episodes of Father Brown, a BBC series, and within the space of four months, hours of music have been written. Every cue is written fresh, exactly like a film. Every cue is spotted, composed to picture, orchestrated and then recorded. We have a large orchestra of about thirty musicians, so it has a kind of filmic sound. A Poet In New York was approached exactly the same way as a film would have been, we spotted it, we had The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra: there is really no difference anymore, it’s exactly the same process, and I’m as proud of it as I would have been, had it been on the big screen. The fact it’s on a small screen is not a problem.

Composer Ben Bartlett once said that TV has to grab the audience away from everything around…

Yes, of course: you haven’t got a captive audience with television, everybody’s not sitting in a cinema with the lights down: they might be making a cup of tea, or on the phone or writing a letter, when the attention of the audience in the theatre is only focused on what happens on the screen. But it doesn’t affect how I think about that when I write music, I just write the best music I can possibly write to suit the film. That even doesn’t enter my head.

Is it important for you to write a memorable main theme for each TV show?

Absolutely. I worked on a series some years ago called Judge John Deed, about a High Court judge. When I started thinking of the theme, I thought it possibly could have quite a long life, maybe one or two series, and that I should write a tune that I could twist and turn in lots of different ways as the story develops, so I wouldn’t get bored of it. The judge has lots of love affairs with lots of different women, so I needed something that I could turn from the main theme, which is quite pompous, into something slightly sexy, romantic. So it was definitely in my mind, as I was writing the theme, that I should write something that wasn’t going to backfire on me. And in the end it went for six series, and I knew that I had a tune that I could work on.

You have a long relationship with the BBC. How are they receptive to music in their productions?

The BBC is such a big broadcaster, and they make so many programs sold all over the world. They have a great reputation worldwide. I’ve worked a lot for them. The project I’m working on right now is called Wolf Hall, and it is a six-part drama for the BBC. It’s very important for me to work for them, they’re very receptive to music. They obviously commission more music than any broadcaster in the UK, just because of the volume of their output and the number of programs that they produce. They want live music, live musicians, they want the music to be of very high standard. So I am very fortunate to have a broadcaster like that. They have no adverts, which is great because your music will flow without interruption. It’s a very brilliant place to be working, because they always want live music and live musicians, as much as possible, unless it’s a very small production… But if it’s a reasonably good-sized production, they want live musicians, which is very important for me, because I was never interested in working with machines, I like to work with musicians.

What can you tell us about your music for Father Brown?

It’s a BBC series about a priest who is an accidental detective at the same time. It’s quirky and in every episode, there is a murder, and he work out who has committed the crime. Father Brown normally gets it right! What’s great musically is that you can tell the audience something they maybe shouldn’t know about the character. It’s great fun, we have a 25 pieces orchestra, and it’s for the BBC, so it’s a high production value, but such fun to work on: every episode is different, in terms of character and murder. I really enjoy it.

Do you have to fight to impose your views in terms of music?

It depends on the director. Some are working with you very comfortably and it is a very good collaboration, it’s very creative, with discussions about the music… I like collaboration, and I don’t mind people having ideas because I can feed of that. Sometimes they have great ideas. The only problem occasionally arises when the director, the producer, the executive producer don’t agree on what the music should be. One thinks the music should be dark and threatening, and the other thinks it should be happy and light… And the one in the middle think it should be romantic or whatever… They can’t agree on a style of music, because they are not sure of what would work best on the program. And that’s difficult because you have to try and find a way of answering everybody’s concerns, and working with everybody’s individual taste.

For you, what is the perfect collaboration with a director?

When they trust that you are going to come up with something they like. When they trust you, it’s open and friendly, and you can collaborate easily. When they have an idea, I can take it on board and they listen to my ideas. It’s like having a really good friend whom you can talk to about your problems. But sometimes it takes time to develop that. With director Peter Kosminsky, it will be our sixth collaboration on Wolf Hall, we’ve established a working relationship over those five projects. When you start with someone new, it can take time, although in the case of the director of A Poet In New York, we somehow immediately got on. And I wrote a theme based on the script and she used it as a temp track on the film. It was a very wonderful working relationship, and that was the very first time we ever worked together. So it’s about personalities, really.

Do you prefer when the directors have some kind of musical knowledge?

I prefer when we talk about the story and the characters rather than talk about saxophones or oboes, or what key is this gonna be in… That’s not helpful. But if you can talk about the color of the music, what it should tell the audience, what it should hopefully add to the film, that’s the best way of talking about music. It’s hard though to describe music, to talk about it. Because this is not something you can write down, and everybody hears music differently, and knows what they like and they don’t like. So it’s difficult, but if you can establish it, it’s better to talk like that.

You’ve worked with Brian Gilbert on Tom And Viv and Wilde. How would you describe your collaboration?

It was a very important collaboration, because it was my first film. I remember playing the music to him: I had all worked out on keyboard and samplers, and I played him the first few themes, the first time ever he came to hear it. And he just said « No, no, no, no. » Almost every cue was « No! » And then I started again and wrote everything on the piano, I played him everything and only at that moment it started to work, and we could collaborate. He wasn’t interested in hearing samples or mockups, or previews of anything. He wanted to hear the music at the piano, to hear the melody and how it was going to work with the picture. Once we had established this relationship, it worked very well. I don’t know if it would work now, because everybody wants to hear music as close as it is going to sound with the orchestra. But at that time the technology wasn’t quite so advanced, and he didn’t like listening to samples, it really put him off. So whatever I was playing to him, he wanted to hear it on the piano.

What memories do you have from your French collaboration on Arsène Lupin?

It was the most fantastic experience. I loved it from the beginning. I loved going to Paris and meeting with the director, I loved working with him. It was the biggest challenge because there was over two2 hours of music in the film, and I was really exhausted afterwards! It was a big project, but I loved it. The director wanted an epic score, he wanted themes, melody, action, drama, romance, comedy… There was everything in those two hours and it was like a workout for a composer! Like going into the gym and working out for all day. It was wonderful, and I wish I could write more for French movies, and working in France again, because I loved it.

According to you, which is the most difficult emotion to express musically?

I would say comedy. I’ve written a few comedies, and I always find it very hard for music to be funny. I prefer music to be dark, I am not particularly into writing funny music, and I am not sure it is ever successful, really being funny. You can have humor and lightness in music, of course, and you can have wonderfully quirky moments, and lights moments. But I don’t like it when you’re writing music for a comedy and you’re encouraged to try to make the music funny. I always prefer to go the opposite way: let the jokes in the film happen and the music can just be deadpan underneath, just flow. I don’t like the music to try force people to laugh.

You have composed so many melodies during your career. Would say it is getting easier or harder?

I think what gets easier is that you have more experience, and if you get something wrong, you know you can go back and fix it. That’s very positive. I’ve never found writing melodies hard, I come up with them quickly. But the hard thing then is working it through the film, and making sure that you can write the full score. That’s a big job of course, but I can come up with those very quickly, in 3 or 4 minutes sometimes, but I might not use them. At the end of the day, sometimes I don’t like it and I start again the next day. There’s a flow of ideas, and then I sort of choose. With Father Brown, I went with 10 different themes that I played to the producers and directors. It was a bit mad, but I read the script and this is what I thought of. And they chose actually the one that they preferred, that was my favorite too, so that was good.

Apart from your love for melodies, another characteristic of your music is immediacy. Does it come to you naturally?

I suppose a little bit, yes. I like the music to draw the audience in immediately, to help them follow the journey very easily, they don’t necessarily have to enjoy it, and sometimes they may not like it, but they can follow the path of the music.

Do you feel sometimes a bit old fashion because themes are not what producers are looking for nowadays?

Sometimes it can be thought of being old fashion having a tune, but I believe in the power of melody, and I think it’s very strong both in film and television. But not every film demands a strong melody. For example, I did a horror movie some years ago called Lighthouse, it was very dark and it didn’t require a big tune. There’s something going on melodically, but not something you would be able to sing. But I like the idea of having a theme, it gives it an identity, it makes an immediate connection with the music. If it’s just some abstract piece, unless it has a very distinctive color, it can be quite forgettable, but if you have a melody, it automatically reminds you of that production.

You used to say that you have the best job in the world. Musically speaking, do you still have dreams to fulfill?

My dream is just to keep writing music. I like the feeling that there is a purpose for it. I don’t like writing music just for myself at home. For a film, a TV series, a song with Don Black, whatever, as long as I keep having this purpose and the opportunity to write for various different productions, then I’m completely happy.

Don Black said that a lot of composers have a dark side, except you…

Don is great, he is a really good friend. A dark side… I think everybody has a dark side, but I try not to… You know, I think working in this business is an honor, and it’s not anything to be worried about. I try not to take it too seriously. It is fun and I love doing it, so what is left to get upset about really?

Interview conducted on July, 26th 2014 in Cordoba by Olivier Desbrosses & Alexandre Lessertisseur

Transcription : Stéphanie Personne

Translation : Olivier Desbrosses

Pictures : © www.debbiewiseman.co.uk, Michael Leckie, Julio Rodriguez

Thanks to Debbie Wiseman for her kindness and availability despite a complicated schedule, and to the entire team of the International Film Music Festival of Cordoba.