![]() CLIQUEZ ICI POUR LIRE LA TRADUCTION FRANÇAISE

CLIQUEZ ICI POUR LIRE LA TRADUCTION FRANÇAISE

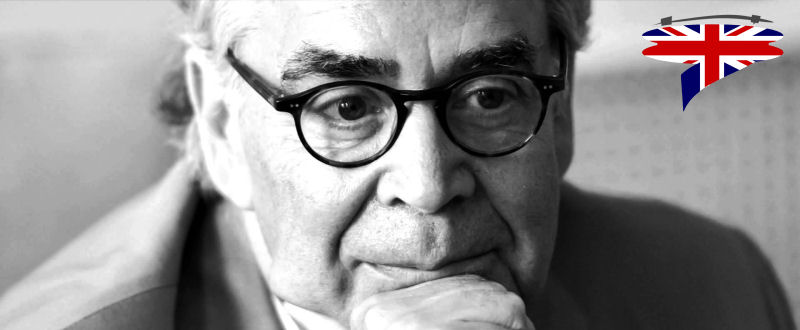

In 2017, October will definitely remain as the month of Howard Shore. The Canadian composer is honored at the French Cinémathèque with the programming of a selection of the films he scored. He opened the festivities on October 9 with a master class of more than two hours where he answered questions from Stéphane Lerouge and Bernard Benoliel. Another big piece of the homage was a symphonic concert which allowed to rediscover an anthology of his work for the big screen. Despite being tired after a long trip from Toronto, Howard Shore was kind enough to meet with us and answer our questions with candor and enthusiasm.

A concert in Paris, a tribute at the Cinémathèque, a CD anthology released by Universal… How do you feel when you look back at your career like that?

I am pretty much energized by it. Stéphane Lerouge did the album and I got to listen to music from over forty years in the making. It was interesting: I write music every day, so I don’t look back that much. So I enjoyed having that chance.

Until you score The Lord Of the Rings, you were often considered as a cerebral composer. Did this huge success change your artistic life?

It was spreading the music around the world more than I have done before. Before The Lord Of The Rings, maybe some people knew some of my music, but now it was going everywhere. And I was conducting the Lord Of The Rings Symphony all over the world for years from the far east and Russia, all over Europe, and in America, Canada, Australia… I think it created interest in the early catalogue as well, the early part of my work.

You wrote a lot of stage music when you were young, but then you went into movies. Why?

My interest was always in music. So going into films was a way to use music and technology, and I was interested in that. As a young musician and composer, I was looking for opportunities to write outside of small groups, I was looking to work with chamber orchestras, symphony orchestras, choirs, I wanted to be in a studio and use the recording technology. I wanted to study the physics of microphones and acoustics, so films offered all of that to a young composer. Over the course of eighty films, I expressed a lot of different ideas that I was interested in for films like Crash, Naked Lunch, to symphonic works like The Fly, even scores like The Silence Of The Lambs or The Lord Of The Rings. I got to express a lot of the ideas I was interested into my music, and this is what I was looking for.

Do you regret leaving the classical music world on the side?

I never really did leave it, I continue to write pure music always, and now I am starting to bring some of that music out. On the album we released last year, A Palace Upon The Ruins, you have chamber music works from the past, things I’ve been working on over the course of years. I have always continued to write. But now I have written a full-length opera, three concertos and two songs cycles, and I will premiere a new song cycle in Toronto with the Toronto Symphony in two weeks.

Would you say that your experience in movies is nourishing your concert music?

Yes, but I think because my interest was in music. I love cinema, I love movies but I was always looking for new opportunities to try and express different ideas in music. Now, having done so much, I am interested in the commissions because they are offering more freedom in some areas and also I was interested in working with different artists. My piano concerto was written for Lang Lang, and it was fantastic to be able to work with a great artist like that on an extended piece, not something too small. I just wrote a piece, a concerto, for the great Montenegro guitarist Milos Kradaglic, a brilliant guitarist. So it allows me to work with different artists, and I love that. I did it in films too: I got to work with Ornette Coleman, or with ZaZ and others artists too on Hugo. It is always fun to do that.

How do you approach a new project?

I like to work with words. As a composer, I like to work with a script, a screenplay, I like to work with the original source material. So, we’ve got a lot of adaptations with Cronenberg , JG Ballard’s Crash, William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch… I did a Shakespearian adaption of Richard III in Looking For Richard, The Lord Of The Rings is all based on Tolkien’s novels… I like to work with the ideas inherited from the words first, and I write music based on those ideas in a more pure way. Then I take this music written for those ideas and I apply it to the film, put it into to the film, and in a sense score the film. I like to watch the film as an audience, so I have the feelings and the emotions not too technical, and that is why I don’t like to work with computers at that stage. I work with pencils and paper, it is very much a visual art to me: composition, harmony and counterpoint. So everything is on paper, and then I visualize my ideas and start to sketch them out. And in some cases, I have written the entire score that way, like Dead Ringers and Naked Lunch, they were all written in that way, away from the film. One viewing, and then, to score the film, I take that music I have written and then place it into the film and orchestrate it perfectly for the scenes of the film.

It is a very linear process: composition first, then scoring and the orchestration, then conducting, performing and recording, all part of film music. It is always the same process, whether it is for a movie, a play or a videogame. The music happens first for me, away from the imagery, just in my subconscious. Because if you think of films, think of going into the cinema, the lights go down, it is dark, the images start to appear on the screen, you hear things… What I am trying to do is get to that world, get to the subconscious, the subtext of the film and write music that is based on those ideas. I think the technic of that is the subtext, the dream state. I always talk about napping during that period of the process, but that is because it is a part of it: it is a way to reach in, to hear your subconscious express the ideas in a more intimate way. The technology doesn’t always allow that if you go to it right away.

Does this process also explain the organic quality of your music?

Yes, whenever I talk to students, I always tell them not to work with computers right away. You can do that later on. But first try to express the ideas. Music is a very vast world, and the computer narrows everything too much too quickly. Allow the vastness to project what’s possible for a while. Then go into that creative state where you can just imagine what the music could be, try to keep that idea and try to express it, capture it.

Looking back at the Peter Jackson movies, how do you feel, now that it’s over?

When I finished The Lord Of The Rings, I never really felt like I had finished. I wrote in that world for so long that at the end, it was hard to put the pencil down and start working on anything that would take me away from it. But then I had a break and I went back for The Hobbit. I really enjoy Tolkien’s writing and his world, so I am never really tired of it. He is a fascinating writer: some people read his books every year, I remember Christopher Lee telling me that he read The Lord Of The Rings every year, and he even met Tolkien. And so every year he got new inspiration from it. People love the book and I fell into the same world because I love his writing, about nature in particular. To go back there was to revisit a world that you really love, and was enjoyable to you. It is fun living in Middle Earth!

You love to work with voices: could we imagine a series of concert lieders from LOTR?

I could, yes. The idea using the voices in The Lord Of The Rings was to create a sense of history. Middle Earth pre-dates our culture by 5000 or 6000 years, so you want a sense of antiquity. The story told was very old. So I was trying to go back to the origins of music which of course is the voice. The singing voice would be the first instrument ever used, then using flutes and fiddles, and strings and irish drums… It was built all the way to create a sense of historical beginning of music. Using it for the opera would be fantastic because Tolkien wrote six original languages for The Lord Of The Rings. So by expressing them and putting them into the choir and children’s choir deepens and broadens the story, in Quenya, Sindarin… That was a really creative fun aspect of it, working with the voices. It is very much a choir piece, for a large symphony orchestra and choir.

If you were scoring The Lord Of The Rings today, would you do anything differently?

I don’t know… The score was written on a kind of day to day process, it was a too big work, it is a twelve hours work. I couldn’t work out the whole structure of it so the way it was created was actually very similar to the way Tolkien created the original story: day to day, week to week, month to month, trying to understand how the story grew and expanded in The Two Towers and concluded in The Return Of The King… So we did a similar type of journey. Something like the destruction of the ring took almost three years to write up to that point. Having read the books many times, I knew I had to write a piece for it, but I couldn’t tell you what that was until about three years of writing. Then, when I finally got to that scene, I could write it completely linearly, it just poured out, I knew exactly how to express that moment. But that took years to be able to do that, so to go back today and change something, I don’t know how I could do that now. I could change things, but I don’t really want to, I respect the thinking that originally went into it.

In The Hobbit, you had to use Misty Mountains, that you didn’t compose. Was it frustrating?

Working on films, there are generally others music added, for example in Philadelphia: there were Bruce Springsteen and Neil Young songs. Working with Scorsese, there is always other music in the film. So it wasn’t that unusual. Even in The Fellowship Of The Ring, Plan 9 wrote some source music that was used in the movie, that the hobbits sang. So Plan 9 wrote for The Hobbit what was essentially a source piece, but it was a good source piece, so it went into the trailer and got into the mind of the film. That can happen, music works in mysterious ways. And since I wrote a lot of music for The Hobbit, the song wasn’t used in the second and third movie.

How did you select the cues for your concert in Salle Pleyel?

I initially did a Hobbit piece that was four movements that opens the concert. The first part of the second half is David Cronenberg pieces: The Fly, Dead Ringers and Naked Lunch (Emile Parisien plays the saxophone). Then a Hollywood type of comedy, like a lighter section with Big, Ed Wood and Mrs. Doubtfire. The thriller part of the concert has David Fincher’s Seven and Jonathan Demme’s Silence Of The Lambs. We also will play a piece of Esther Kahn from Arnaud Despleschin. Then we go into Martin Scorsese: we play The Aviator, music from Hugo, with Zaz. And then we go back to Peter Jackson with The Fellowship Of The Ring and Return Of The King. So the concert is kind of structured with directors and different movies to express different ideas in my career.

Interview conducted on October 5, 2017 by Olivier Desbrosses, Florent Groult and Stéphanie Personne

Transcription : Olivier Desbrosses

Huge thanks to Howard Shore, Stéphane Lerouge, Élodie Dufour and the entire team of the Cinémathèque Française