![]() CLIQUEZ ICI POUR LIRE LA TRADUCTION FRANÇAISE

CLIQUEZ ICI POUR LIRE LA TRADUCTION FRANÇAISE

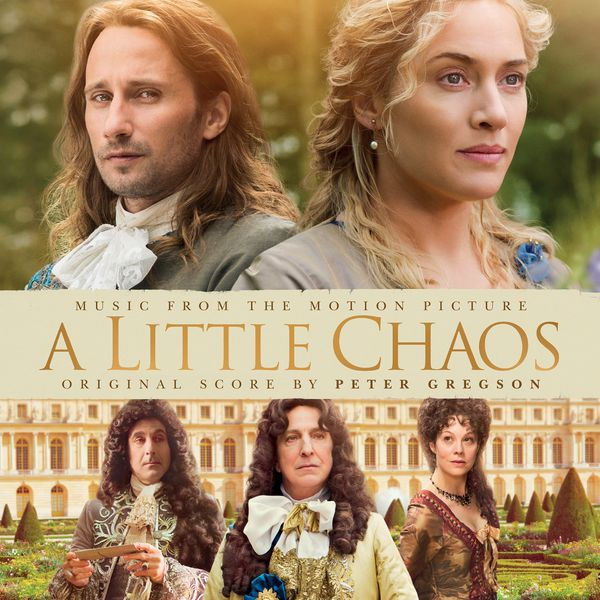

Born in 1987, Peter Gregson is a cellist and composer whose young career already proves surprisingly dense. As an instrumentalist, he contributed to the creation of works by many composers from the contemporary scene: Tod Machover, Gabriel Prokofiev, Max Richter, Jóhann Jóhannsson, Steve Reich, Sally Beamish … He also composed for ballet and released several solo albums: Terminal in 2010, Lights In The Sky in 2014 and Touch in 2015. For the world of movies and television, he has been chosen to play the cello (acoustic or electric) for many composers: David Arnold (Sherlock), Dominik Scherrer (Ripper Street), Dominic Lewis (Spooks: The Greater Good), Lorne Balfe (Sons Of Liberty, Terminator Genysis and 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers Of Benghazi), Roque Baños (In The Heart Of The Sea), Hans Zimmer (Kung Fu Panda 3) … But it’s Alan Rickman who gave him, in 2014, the opportunity to compose for a feature film with his second experience as a director, A Little Chaos. Today, we offer you this interview with Peter Gregson, his last musical partner, as a tribute to this great artist whose death on 14 January 2016 has left orphan the entire world of cinema.

What is your first musical memory?

My first musical memory would be, probably at the age of 3 or 4, going to a children’s concert in a symphony hall in Edinburgh, where I am from. I had seen the James Bond film where he’s skiing in a cello case (The Living Daylights, editor’s note) and I said “I want that!” And when my parents took my brother and myself to this concert, I saw a cello case and I said to my parents: « I want that! » I think that romantically, I remember the concert being the Elgar Cello Concerto, but in reality it was probably Peter And The Wolf. I remember being captivated by the cello case. And my mom said: « If you want the case, you should probably have a cello. » And I just sort of got interested in cellos.

Is there a musical work that has changed your life?

In contemporary classical music, there’s a piece written by George Crumb called Black Angels, which is a string quartet. It’s the most unbelievable overuse of the instrument, so incredibly well written! It’s very dark, a very heavy political piece about the war. It had a great impact on me because at that age, when I first heard it, cello players were all about making beautiful, pretty sounds, and being very controlled, a whole different kind of control. And I got completely obsessed with how these instruments, which I knew played Bach and Brahms and other beautiful things, could also do that thing. From that point, I really got into contemporary classical music, which led to the work I do on films. But it all started with: « How do you make that sound? »

As a cellist, how did you end up working on movie scores?

It came about through having a very obsessively focused set of techniques. I was working with a lot of experimental contemporary composers, and you end up having to invent sounds, a little bit like a synthesizer. You have to imitate things and find ways to make sounds. I just started doing that for a couple of people, friends from college who were writing, and then one got a TV show and it kind of snowballed, but all the while really focusing on this one thing. I do a lot with electronics as well, electronic cellos, sound processing. And one thing led to another…

Are you influenced by other film music composers?

There’s a lot of risk to listen to other people’s music. I listen to loads of things, to everything I hear about, everything I’m told about. And I spend a lot of time on playing. A lot of time! But it’s dangerous, when you’re writing a score, to listen to too much stuff that you think might work. It is like inflicting a second temp track on yourself. For A Little Chaos, I remember originally thinking “It will be great, I got to listen to amazing baroque, amazing French music, Lully and all that brilliant pieces.” But I didn’t realize it was the worst thing I could do. There’s nothing worst than a bad ripp-off of Louis XIV’s type of music, a pastiche of that. Ultimately, you must respond to the picture on the screen. I listen to all sorts of things, not that much film music. But if I do, it’s not for a specific reason. I think that Daniel Pemberton’s music is brilliant, he does amazing things with synths. What Carter Burwell or Craig Armstrong do is quite brilliant too, they are people that I admire and respect. But I wouldn’t listen to that if I was scoring a film.

Is there an emotion more difficult for you to express in music?

I think comedy is the hardest thing to write, happy film music. For the record, I’ve never actually successfully done a comedy film. Because I play the cello, I write sad music. But I think the issue with funny music is that you don’t want to tell the same joke twice. If you are watching a funny scene, and you’ve got the punchline and the music, it’s like too positive. It’s obvious, spoon feeding. That’s difficult, really tough. The best example for me of a great comedy score is Team America, because it is serious action music, it’s the perfect score for that funny film. It’s like when you’re cooking a dessert with chocolate and then you add a little salt, and then… it’s absolutely amazing! Not all of the ingredients in a cake are sweet, but some will improve the cake. Flour is not sweet, but it’s important, the building part is really important. What I’d love to do is to score a comedy with absolute freedom and a never ending budget, and to try it safely with no risk to get fired. I would have no idea where to start for a comedy, but I love watching them! But I really love the kind of music I get asked to write, the kind of auteur type, character driven, drama type of films, trying to make the music like another voice, another character, in the film.

How did you end up scoring A Little Chaos?

It’s quite a nice story. A cello piece had been written for me by Gabriel Prokofiev, who is Sergei Prokofiev grandson. It was then choreographed by the English National Ballet. And the choreographer from that asked if I would write music for his next ballet. So I dutifully wrote a ballet about water, which was complicated, but it’s a beautiful piece, stunningly choreographed. And in the audience, one night, a preview night, Alan Rickman was sitting there in this tiny little theatre. He came to me afterwards, and he said to me: “I’m doing a film, do you want to do the music?” He heard 23 minutes of quite electronic music, fast, functionally irrelevant to the score that we ended up with for A Little Chaos. But he liked the fact that the music was not loud, not overpowering the scenes, it knew its place. So he kept coming back to that over the year of working on it.

This was quite an opportunity!

Someone has to give you an opportunity to do it sometimes. I think that there is a series of points that come together. I really wanted to write for films. I was playing a lot on other people’ scores. I actually had a lot of experience playing with a lot of other composers, as a cellist. But I didn’t have any credits to my name, so all the credit goes to Alan… In the music community, we actually need people to stick to their decision, who don’t go towards the safe and easy choice! Alan Rickman had heard whatever he had heard and liked something, and he went with his decision! I don’t believe he is the only person who has strong opinions. I really hope that other people have that kind of convictions. As a life lesson, it is amazing to think that someone would do that, when a person really goes for it! It’s tough to get your first feature… It’s not like saying « Hello, I can write music for strings for you, would you like me do that? Thank you. » (laughs) Someone has to ask you, but nobody wants to ask you if you haven’t done it before, it’s tricky.

What was your scoring process with Alan Rickman?

I was very lucky that he came to this ballet about two or three weeks before they finalized the script. We spotted the film to the shooting script. There was some music needed on set, some choreography that needed music, so I got to write that. I was very involved through pre-production. And then, when they finished shooting, there was no temp score. So I was writing music to pictures as it was coming in. And then we spotted it again. On my original script, the spotting notes are more or less what we ended up within the final cut of the film. Although the film changed shape any number of times, the key moments, when the music comes in, are very close, it’s quite scary. I wrote largely from home, as I didn’t have a studio at that point. And towards the end of the process, I did get a studio. I was going to the cutting room a couple of times a week, taking music in, sitting with the editor, Alan and myself, to discuss music issues. He was very hands on, but it was a very traditional “you work yourself into the ground” kind of process. Once we had the whole film laid out, he would come to the studio and we would try things. Alan is a very musical man, he doesn’t have the musical language, but he cares a lot about the music. I was very lucky that he was so passionate about the music, he really helped it be another voice in the film. And I would be very lucky if I have the chance to work again with another director who cares about music as much as he did.

Interview conducted on October 24th, 2015 during the Ghent Film Festival.

Transcription : Christophe Maniez.

Many thanks to the Film Fest Gent team..