![]() CLIQUEZ ICI POUR LIRE LA TRADUCTION FRANÇAISE

CLIQUEZ ICI POUR LIRE LA TRADUCTION FRANÇAISE

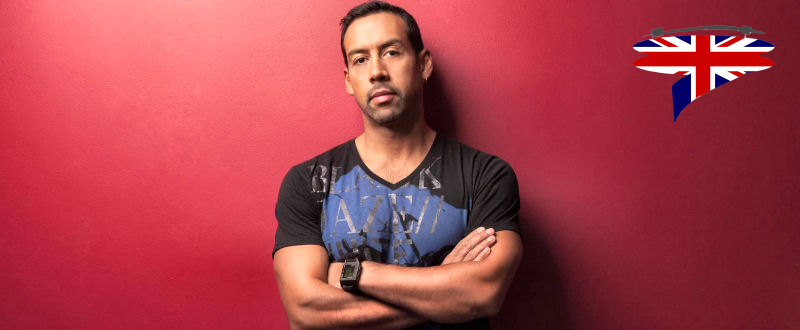

Jazz drummer since the late 90s, the Mexican Antonio Sanchez has enjoyed a meteoric rise, collaborating among others with Pat Metheny and Chick Corea before embarking on a solo career leading to several albums very well received by jazz lovers. He also composed in 2014 his first film score for Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Birdman, earning several nominations including the Golden Globe Award for Best Original Sscore and the British Academy Film Awards (BAFTA).

How did you end up scoring Birdman?

I’ve known Alejandro for a number of years, because he is a big fan of a band that I’ve played with, and because I have played with the amazing guitar player Pat Metheny. He came to one of our concerts in 2005 and then we chatted afterwards and he told me he really liked what he’d heard and seen. And then, I kind of stayed in his psyche somehow, and then in January 2013, he called me out of the blue and said « Look, I’m working on my next film, it’s going to be a dark comedy, and I think it would be great if the original score was just drums. Do you want to do it? Yes? No? » I said: « Yes! » « Okay. I’ll send you the script. » And he hanged up the phone. He sent me the script, I read it and we started talking about it, and little by little, we started figuring out a way to make this happen.

What was your collaborative process with Alejandro González Iñárritu?

It was very unorthodox because usually, the filmmakers use temp music, then they send you the film, you hear more or less what they did and then you start creating from there. But this time around, we started doing the temp music ourselves. So, before they even started shooting the film, we had already gone to the studio and recorded a lot of demos. Alejandro would just describe every scene of the movie to me in great detail, and he would just have me play. So I would tell him: « Okay, why don’t you sit right in front of me, in front of my drums, explain the scene to me and then close your eyes… » So he would tell me: « Okay, in this scene, Michael Keaton is in his dressing room and he gets up, and he opens the door, and he starts walking through this hallway, and then he turns around and his mind is going all over the place, and then he opens the door of the stage and he knocks, and he’s in there and then the actors are there… Really long scenes. So then he would sit in front of me, with his eyes closed, and as I would be playing, I would tell him to raise his hand whenever the next phase of the scene happens. I would be improvising and then I’d see him doing a sign and that was « That means that he opens the door » and then I would play something to accentuate that.

We must have tried sixty or seventy different takes of each scene like that. No sixty takes of each scene, but sixty or seventy takes of the whole film. And they grabbed those demos and they used them on the set to rehearse, to give the actors an idea of what the rhythm was going to be like for each scene. Then, they spliced those demos, they put them on the rough cut of the film, so that ended up being kind of the temp music. Then they brought me back to L.A. and they showed me what they did and I had to kind of re-learn a lot of the things that I had done that they had liked, and for the things that they hadn’t liked, I had to come up with other things. But the whole process took maybe two and half days. It was very, very fast. The whole thing took 28 days to film, so everything was very fast.

For the final score, did you play over the full movie or did you take each scene separately?

Each scene separately. Once I went back to L.A., they showed me the film and then we would focus on each scene that had drums until we got it right. And, of course, now that we were looking at the film, Alejandro would have a lot more specific things to say about dialogue, about movement…

Listening to your music, we get this feeling of spontaneity, like it’s an improvisation on the set…

It was an improvisation because that’s what Alejandro wanted me to do. In the beginning, I tried to send him some demos that were a lot more organized and predetermined. And he said « No, no, no, no. I want something jazzier, more organic, more spontaneous », and when he said that I thought: « Okay, well, that’s going to be really easy because that’s my specialty, that I can do very easily. » I think I used the same set of instincts as when I play with a band and improvise with them, or improvise by myself. To approach this, I used the same set of my brain where it’s just like « Okay, instead of reacting to the musicians, I’m reacting to the image and to the actors and to the plot.” And he would have things to say later: « Okay, when you hear him saying this word, stop there, and then when you hear this other word then start but faster, and when you see him hit the wall, I want something big there, and when you see him opening the door I want something there too…” It was this kind of directions, not very technical, he’s not a musician, but he’s got a great musical mind. So, to work side by side with somebody who is in a completely different discipline than I am but has such a strong vision creatively speaking, it was so much fun, it was great. That was the best part for me. I think he is a frustrated musician, a frustrated drummer, because every time after I would play, he would just look at me and be just like « Man, you’re so lucky. » And I would be like « Yeah, I think you’re lucky too. » (laughs)

Do you act as the drummer in the movie?

That’s not me. I recommended this really good drummer, who’s a friend of mine, his name is Nate Smith. But I was on tour when they shot those, so I couldn’t be there unfortunately.

So you had to match your improvisation to his own?

Yeah, that was really hard actually, because he improvised whatever he improvised, and then when it was time for me to record those scenes, I had to match exactly what he did, so I had to learn his movements and see the orchestration that he used. So I would have to learn, and then whenever I would see him, I had to remember exactly what he played and match it and then keep playing my thing afterwards. So that’s what basically took the longest. Alejandro was so strict with it that he would see and say: « No, I can still tell that it’s not him playing. » So we would do it again and again and again until he was convinced that it looks like he played the music.

Would you like to do it again, to score other movies?

I’m going to do another movie next year. But I have to be honest, for there to be another Birdman is going to be very difficult. What I liked the most about Birdman was that I was able to do what I do, without having to do anything different than what I usually do and what I am as a musician. I think that it is why it works so well, because I wasn’t forcing myself to be somebody different, that I am not.

Interview conducted on October 24th, 2015 during the Ghent Film Festival.

Transcription : Milio Latimier

Many thanks to the Film Fest Gent team..