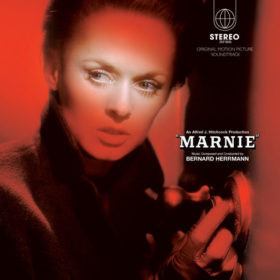

On July 6, 2007, Joel McNeely conducted in Lyon a concert of the music of Bernard Herrmann, during Les Nuits de Fourvière Festival. Called A Nightmare Romance: Bernard Herrmann & Alfred Hitchcock, this show produced by Danny Kapilian was performed previously at the Barbican in London in March 16, 2006. It has been performed again in Chicago on April 4, 2008.

In the haunting set of the ancient roman amphitheatre of Fourvière, we were lucky to enjoy the music from Psycho, North By Northwest, Citizen Kane, Farenheit 451, Vertigo, The Trouble With Harry, Marnie and Taxi Driver. The National Orchestra of Lyon and a jazz quintet performed the music, accompanied by scenes taken from the movies and a narration by the actor Philippe Morier-Genoud serving as a guideline and made up of excerpts from Steven C. Smith’s brilliant biography, A Heart At Fire’s Center : The Life And Music Of Bernard Herrmann.

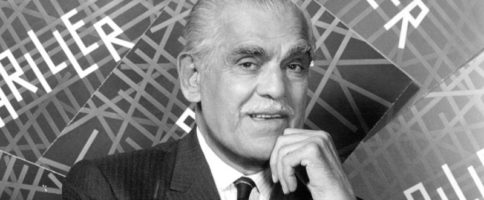

On the same day, just before noon, we met Joel McNeely for an informal interview taking place right after the last rehearsal with the orchestra. The sun was high in the sky and we were waiting for the composer behind the stage of the amphitheatre. After a couple of interviews with the local press, the composer took us to lunch, saying «I wanna get some food!» While waiting for Joel, we started a little chat with Varèse Sarabande’s big boss, Robert Townson.

Retrospectively, how do you see the evolution of film music?

Robert Townson: Well, you know, film music like all arts is going to be evolving and it’s going to go through stages where there’s a real metamorphosis that happens. You can see that throughout the history of film music: from the golden age, when the influence was largely European, composers came from Germany, Austria, Hungary, that really accounted for the first generation of film composers, and that ended up evolving with an american group of composers like Bernard Herrmann, Alex North, who brought their own very unique sound and styles. They changed the art form very considerably. If you look at what film music was before A Streecar Named Desire and what happened after, which kind of laid the groundwork and allowed for composers like Jerry Goldsmith and Elmer Bernstein to come in and do their thing. And then of course you have the years of Jerry and Elmer, doing their thing which paved the way for another generation to come in, composers who were directly inspired by specific scores and more general styles.

Do you see a new generation of composers emerging today?

Robert Townson: Absolutely, I mean, Joel has been doing it for a while now, and today young composers like Brian Tyler… (the interview briefly stops, time to join Joel for lunch !)

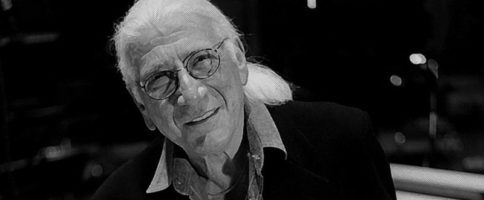

So, what did you think of the orchestra?

Joel McNeely: They’re wonderful. We’ve rehearsed four times now. We are in pretty good shape for the concert tonight.

How did this concert of Bernard Herrmann’s music happen in Lyon?

Joel McNeely: This was related to the concert that we did last March at the Barbican in London. Bryn Ormrod, who presented this concert at the Barbican, had a relationship with the Fourvière Festival, and asked if they would be interested. We are in Lyon this year and we will do the same concert with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra next year.

Is it the first time you come here in France?

Joel McNeely: The first time in Lyon, but not the first time in France. In fact, I used to come in France when I was a playing musician.

Obviously, France must be a favorite for a gourmet like you who appreciates the cuisine and wines…

Joel McNeely: It is! You know, I started cooking. But I haven’t had a chance to experience Lyon, we’ve been so busy … Maybe tomorrow!

On your website, you mention the name of Rayburn Wright, who was an important educator in your life as a musician. Can you tell us about him?

Joel McNeely: I think everybody, if you’re lucky, has at least one great teacher. Somebody who changes your life, somebody who puts you on a path… I went to Ray after four years at the University in Miami, a jazz school, very good for jazz, but in terms of composition, I wasn’t learning what I needed to learn. So Ray took me and said «Ok, I have two years with you, you’ve got a massive stuff to learn and I’m going to teach you». I didn’t sleep very much at all for two years… I studied jazz and orchestration with Ray and composition with Christopher Rouse. He was great, he’s still a good friend, we keep in touch.

Which works of the repertoire would constitute your personal pantheon?

Joel McNeely: It’s so hard, there’s so much… But if you look at my collection of scores, the ones that start falling apart, certainly The Rite Of Spring, this one is really falling apart and I need a new one! Also, almost all Ravel, Debussy’s La Mer…. The 2nd, 5th and 9th symphonies by Mahler… Right now I am really into Beethoven’s piano sonatas… There is so much music in there… When you study them all as one work, it’s got the world in there! Everything in music is in the Beethoven piano sonatas, I think…

So, despite a busy schedule, composing, conducting, teaching, you give yourself enough time to study scores and you continue to learn?

Joel McNeely: Honestly I do not listen to a lot of film music, but I go to a lot of concerts. You know, it’s not so much that I don’t listen to a lot of film music, I don’t listen to a lot of music, I hardly ever listen to music… When you’re doing music for a task, for a very long day, ten or twelve hours a day, you’re not gonna go in and put on music… When I’m not busy, I find myself listening to things that are not related, like Brazilian music, theatre music, I love musical theatre.

Your last film score, I Know Who Killed Me, is a thriller. A genre in which you haven’t expressed yourself a lot. How far can you go in terms of musical complexity and modern music? Did you have the opportunity to experiment?

Joel McNeely: A little bit. Bob Townson and I were talking about this last night at dinner. I feel pretty contradicted. I think you can come wrong about this. But I’ve got a very real sense that, stylistically, complexity is not desired by the filmmakers right now. They want simple, simple, simple. So the truth is, when I was writing this movie, I felt I had to an extent to keep the breaks on. Keep it simple. I could have gone completely nuts and complex with this movie, I kept it medium.

How far would you go if you had a complete creative freedom?

Joel McNeely: I’ll go as far as I’m able! As far as my abilities… I would have absolutely made it as weird as possible. I did one thing, just for myself and the record, for this very reason. I had a little bit extra time to write at the end. So I said, «Ok, just for the record». The movie has a subplot about a piano teacher. I wrote this piece for the album called Prelude For A Madman. It’s just a minute long. I wrote this very avant-garde piano, very technical and crazy. So, I did that just for myself, for Bob and the record.

Robert Townson: You know, it all comes down to the atmosphere that’s being created for the composer by the director, how free they are and comfortable experimenting. And that has changed over the years. I was doing a lot of rerecording in the late 1990s, like Patton with Jerry Goldsmith. We were recording one of the marches and I was like «Oh my God, what a remarkable piece»… At that stage, even Goldsmith was aware that he couldn’t do what he used to do because the climate has changed.

Joel McNeely: Think of Planet Of The Apes… If somebody walked in with Planet Of The Apes today, he would be fired on the spot…

Because there are elements from Stravinsky, Bartok, Varèse and Alex North ?

Joel McNeely: Not only that! He created the first synthesizer sound without ever using a synthesizer. All those sounds sound very electronic when they are completely acoustic.

You once expressed your disappointment at not being able to go further musically in the movie Virus…

Joel McNeely: I’ll be right another time… (laughing)

In your first collaboration with Reverge Anselmo, Lover’s Prayer, we can feel that the freedom you enjoyed has enabled you to write a very beautiful music…

Joel McNeely: There is a very strong reason for that. It’s the only time that I’ve done a film where the director just said «Go!». I played him the theme, he approved it, I never did any mock-ups of the cues, I went to London by myself, he didn’t come. I was completely on my own, I could do whatever I wanted! We spent the whole sessions not worrying about if something was hitting a cut, but whether the phrase was beautiful, whether the phrase was musically thought. And that is what you hear when you listen to that record, that we were thinking about the music, not how to hit things… I like this score, it is one of my favourite score. We made two films with Reverge, the other one is called Stateside.

A biographical movie…

Joel McNeely: Well, that is Reverge! He enlisted in the Marines and went to Lebanon, he saw some bad stuff in there, when the American embassy was bombed. So that was his story.

The musical approaches are different in each film : in Lover’s Prayer, music has an important role and in Stateside it is more understated…

Joel McNeely: This is simply a matter of budget. There was no budget for an orchestra on Stateside. I did everything in the studio, and it is very hard to do. 75% is electronic, it’s me playing everything, and it’s hard! It takes time to find the right sounds. It’s very time consuming.

What about your concert music? When you compose without images, without constraints, without delay, what kind of music do you enjoy writing?

Joel McNeely: This music is just what I want to hear, I’m not thinking about influences in particular. For the piece I wrote for my wife (Three Portraits For Violin And String Orchestra), Margaret Batjer, I was thinking about the audience of the L.A. Chamber Orchestra. I’ve been to all the concerts for the last ten years, I know who the audience is. So I wanted to write a piece that the audience would like, I do not want to write something that’s going to alienate the audience and make my wife look bad, because she is the soloist and the concertmaster. Everyone knows and adores her, it would be quite awkward if someone said to her «Did your husband wrote…that?» So I wrote something that the old ladies would enjoy (laughing)… When I think especially about the last performance in Houston, that I got to conduct, I thought it was successful to me, it did what I wanted to do musically, it made me happy but also reached people who may not have a very sophisticated ear.

Please tell me there’s going to be a record for this…

Joel McNeely: Well, I’m gonna try… You have to speak to Bob Townson about that…

(all the eyes turn with a mischievous smile to Robert Townson)

Robert Townson (smiling): We’ve done Korngold, we’ve done Rozsa, time for McNeely!

Joel McNeely: Actually, I thought of doing it in Houston. The chamber orchestra had got a funding to do a DVD project that they would film and record in high definition. You can have the option of having the score just played, beneath the image. So you can follow along with the music. And there would be DVD extras that take certain portions, and it’s played while you’re looking at the score and you can see how it relates. And on that same one they want to the Beethoven triple concerto and do the same thing. So you watch it by itself or can you can watch it with a split screen with the score and the artists. In the case of the Beethoven triple, if you’re a violin student, you can switch from full score to the violin score, with the bowing of a particular artist, in that case Margaret’s bowing. Then they’ll show a rehearsal of the trio and their musical decisions. That’s a very interesting idea. Well, I think it would be very educational for young kids.

In one of the Three Portraits For Violin And String Orchestra, there’s a big influence of Celtic music, you have a real affinity with this music, as one can hear in your early scores.

Joel McNeely: I grew up playing the penny whistle as a youngster. Later I became friends with some of the best bluegrass musicians in the United States. Bluegrass music and Celtic music are totally related. The Celtic musicians who settled in North Carolina formed the roots of bluegrass.

Bluegrass music is prominent in The Fox And The Hound 2…

Joel McNeely: Yes, I had the opportunity to work with musicians such as Mike Marshall, one of the greatest mandolin players on the planet, Jerry Douglas… That was pretty cool!

In Iron Will, there is something special about your writing in rhythm and harmony, which bound them to folk music…

Joel McNeely: That was Charles Haid, the director, a very good friend of mine. He’s a real Irish boy! He’s totally in Irish music and made me listen to a ton of records!

That motif at the base of the main theme, is it inspired by Irish folk music ?

Joel McNeely: The theme is mine but starts off as a jig (he sings the theme and beats the rhythm with his hands), a jig that we could play with a penny whistle and bodhrán…

Do you have time to orchestrate yourself and do what you want in terms of orchestrations?

Joel McNeely: Not in the animated movies, it is just too hard. There are so many notes… It’s a lot of time… But my sketches are very complete. I do a twelve line sketch, sometimes they can copy from my sketches. So I orchestrate when I have time. This was the case for I Know Who Killed Me, the orchestration was credited to a certain Josh Grant… It is the name of my son…

Do you still enjoy writing for animated movies?

Joel McNeely: Oh yeah !

Each film seems to present a different challenge…

Joel McNeely: Yes, I had a great time on the last one, Tinkerbell, it’s very gratifying.

Will we get a record for this one?

(We turn to Bob Townson in a roar of laughter…)

Joel McNeely: I have no idea…

Robert Townson: Each company has its own policy in this area. In the context of a label who wants to sell score albums in quantity, like pop albums, the reality is : it doesn’t matter how good a score can be, how successful it is in the film, if it doesn’t sell, they are right no to sell it, it in the nature of the business. But when you change the context, when the focus is «we want to preserve as much great music as we can» and sell as much as possible, the game changes completely.

There is a strange paradox though: more and more people are aware of the power of music in films, and more and more people are aware that there is now a long history of excellent music that has been written for cinema. So, in a way, the policy of some companies maybe in contradiction with what people expect…

Robert Townson: It’s not unusual though if you think of the big change that’s been happening in the last thirty years… When you go back over thirty years ago, there was no Varèse Sarabande at all. Very few scores were being released. When I started producing my first album in Canada, it was specifically an answer to the fact that there was almost no soundtracks being released, and realizing that even the great composers, Jerry Goldsmith, Alex North, Elmer Bernstein, John Williams, did not have many of their scores released. So I decided that it was not right, and I wouldn’t wait for somebody else to do it, I would do it myself… and that was like 860 albums ago, for me. That’s a lot of film music!

Is it harder now to produce a score album or easier?

Robert Townson: Well, it depends of the context, it is what it is. There is a lot of music being written and a lot of music I have to preserve, by Alex North, Jerry Goldsmith, Georges Delerue, so many of my favorite composers. Between releasing classical scores from the past and recording music from all my composer friends on the new films, and doing new recordings of classical scores. There’s still so much to do!

Discography of the rerecordings conducted by Joel McNeely for Varèse Sarabande

|

Citizen Kane (Bernard Herrmann) Royal Scottish National Orchestra The Day The Earth Stood Still (Bernard Herrmann) Fahrenheit 451 (Bernard Herrmann) Seattle Symphony Orchestra Marnie (Bernard Herrmann) Royal Scottish National Orchestra Psycho (Bernard Herrmann) Royal Scottish National Orchestra The Three Worlds Of Gulliver (Bernard Herrmann) Royal Scottish National Orchestra Torn Curtain (Bernard Herrmann) National Philharmonic Orchestra The Trouble With Harry (Bernard Herrmann) Royal Scottish National Orchestra The Twilight Zone (Bernard Herrmann) Vertigo (Bernard Herrmann) Royal Scottish National Orchestra

|

Hollywood ’94 (Various) Seattle Symphony Orchestra Hollywood ’95 (Various) Royal Scottish National Orchestra Hollywood ’96 (Various) Royal Scottish National Orchestra Amazing Stories (John Williams) Royal Scottish National Orchestra Body Heat (John Barry) London Symphony Orchestra Jaws (John Williams) Royal Scottish National Orchestra Last Of The Mohicans (Trevor Jones & Randy Edelman) Royal Scottish National Orchestra Out Of Africa (John Barry) Royal Scottish National Orchestra Rebecca (Franz Waxman) Royal Scottish National Orchestra Sunset Boulevard (Franz Waxman) Royal Scottish National Orchestra The Towering Inferno (John Williams) Royal Scottish National Orchestra

|

Interview conducted on July 6, 2007, by David Hocquet & Bertrand Huet.

Transcription : David Hocquet.

Pictures : © David Hocquet & Olivier Desbrosses.

Our gratitude and warm thanks to Joel McNeel and Robert Townson for this memorable moment and a wonderful concert.